London

CNN

—

Lucy Jones painted her first nude self-portrait at 50. She was in New York with her husband Peter Leach, she said, when he “took a picture of my backside. I thought, ‘Well I don’t look too bad from the back, so maybe I’ll paint it!’”

Jones is sitting on a wooden chair the middle of a white-washed gallery space, surrounded by a collection of her own works spanning decades for the opening of a new self-portraiture show in London. While the piece in question, “Being 50,” is absent from the exhibition it is striking enough to remember off by heart: an inky black canvas split in two, with Jones’ tilted gait rendered nude in two separate images.

The study of the artists’ front is flat and naïvely painted — her right arm bent backwards at an awkward right angle. (Jones was diagnosed with cerebral palsy — a lifelong brain disorder that permanently affects body movement and muscle coordination — as a young infant.) Her back profile, however, is more elegantly shaded with her spine gently curved to the left, hips following. An image of a wooden cane pokes up from the bottom to divide the painting while a floating constellation of deviled eggs looms above her head — a nod to menopause and losing her fertility.

Painting nude is not Jones’ usual approach to documenting her physical form. In fact, after her 50th portrait, she didn’t create another one until sixteen years later. Why? Because she was finally a pensioner. “Lucky me!” Jones laughed, as she spoke with CNN in the gallery. “At last, I’ve made it.” She was still painting herself, however — on large canvases with a fearless approach to color. These are the reflections of Jones we glimpse in the show, who despite her obvious talent “didn’t really expect anybody to ever be interested in (my) self portraits,” she said. “But it was a way for me to keep drawing.”

In “totally, completely, and absolutely Lucy Jones,” the artists’ physical disability is rendered in bright, brash Hockney-esque colors and confident, expressionist brush strokes. “Most art historically never mentions disability,” said Jones. “But I’ve been really quite interested to bring that onto the canvas. And over the years I think I have.” Her walking frame and cane are repeating motifs, as are backwards words and sentences — a nod to her invisible struggle with dyslexia, and an attempt at sharing that experience with her viewers. “I usually do mirror writing on the painting to make it awkward for the audience to decipher it,” she explained. She often appears with stiff, distorted hands. Hands, Jones said, are the window in the soul. “They express so much of the person,” she said.

Jones’ wit shows through in the titles of her artworks, which often refer to her experience as a person living with disabilities. In “It’s a Long Way to the Bottom of this Canvas” (2000), Jones is suspended in the top right corner, her glasses and cane woefully mid-flight down the painting. “It could be a metaphor for life,” she said. “Or for me, walking, anywhere. It’s a long way.”

There’s a sardonic edge slicing through the work. The title of her 2018 piece “With a Handicap like Yours…”, is lifted verbatim from a conversation Jones once had with a doctor who, after Jones complained of her lack of dexterity, was reluctant to give the artist physiotherapy for her hand. In Jones’ mind, the phrase also translated to ‘What do you expect?’

“He was a lovely doctor, I’m not criticizing,” she conceded. “But it was an old-fashioned expression. I wanted to poke that a little bit.” In the work, Jones is on the brink of an eye roll, her face angled towards the viewer in an exhausted stare. As a retort, she painted a third hand reaching into the painting — a surrealist quip. “(My art) gets more and more confrontational because I want to comment to the world and make them think about disability and different types of disability,” she said.

The earliest work in the show dates back to 1996, when Jones could work on larger, more monumental pieces and stand for longer periods of time. “The idea of standing doesn’t appeal to me anymore,” she laughed. Now, the artist paints on her knees, which has meant downsizing her canvases to ensure she can “still reach the top.” The discomfort from being on her feet means Jones must also now paint her self-portraits from photographs, instead of in front of the mirror.

She called Matthew Flowers, the British art dealer and managing director of Flowers Gallery, “brave” for staging her show. Not just because it centers someone like Jones so audaciously, but because Flowers rebukes the industry’s perpetual appetite for novelty and constant creation. “They’re not all new paintings,” the artist said. “Most of them go back a long time.” For Jones, creating an entire new body of work for a gallery show, when a single painting takes her three months, is unthinkable.

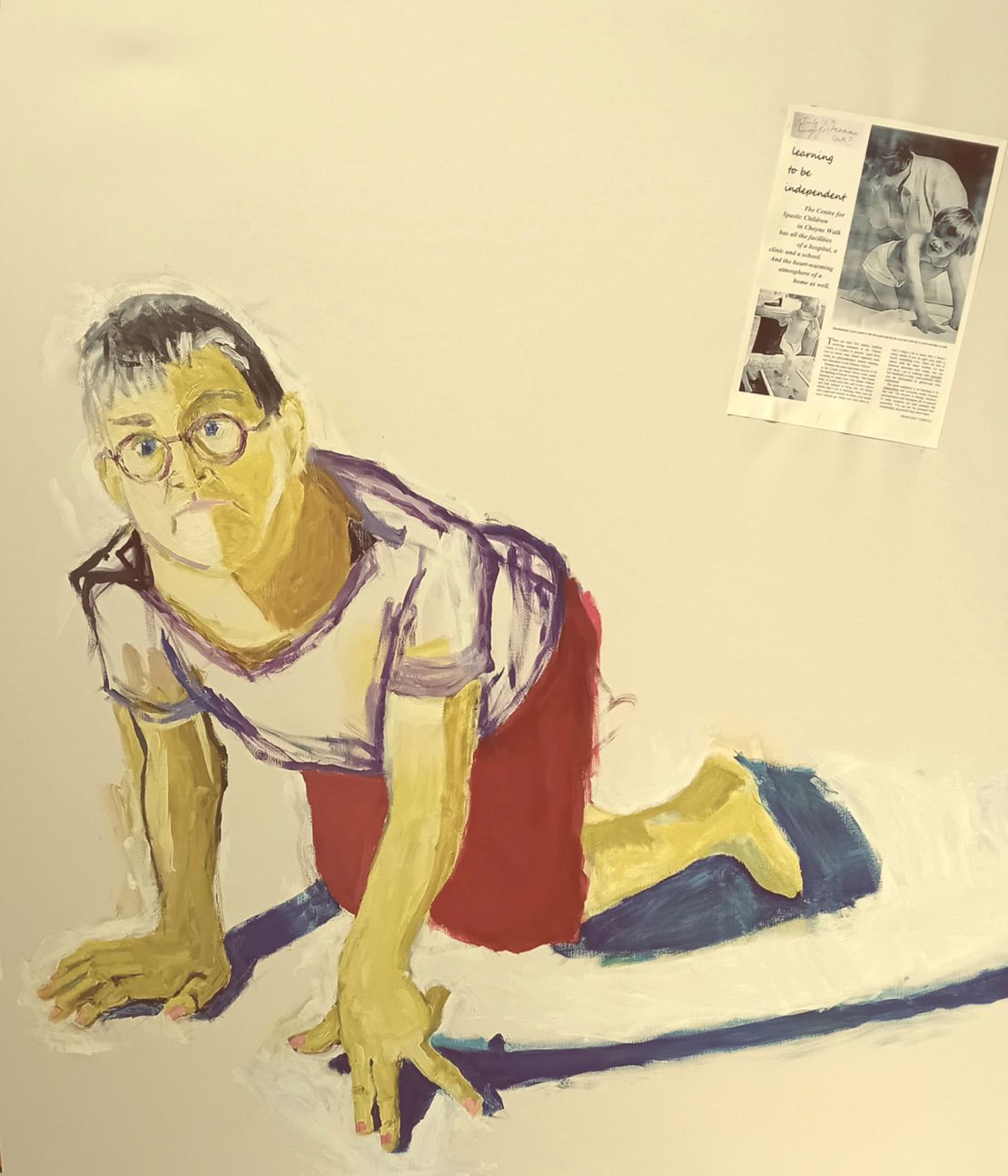

Her newest piece, created this year, is the third in her age-based trilogy, marking the artist at 70. The work shows a self-portrait of Jones on all fours looking up at the viewer, while in the top right corner is a clipping from a leaflet attributed to The Centre for Spastic Children in Cheyne Walk. On the leaflet, a photograph of Jones shows her again on her hands and knees — this time at three years old, learning to crawl for the first time. Jones does not see the parallel as a melancholy one. Seventy is its own milestone, and many surprising, wonderful things have happened in between, she said. For Jones, reaching this point “is a shock” because “I didn’t realize that with cerebral palsy you deteriorate. And let me tell you, you do. Which is rubbish, actually. Complete rubbish.” What age might she like to commemorate next, 99? “99!” She laughed. “Paint myself in a coffin or something.”

“totally, completely, and absolutely Lucy Jones” runs until August at the Flowers Gallery in Mayfair, London.