CNN

—

In the old photo studios of Lagos, Nigeria, negatives were being burned. No longer needed or wanted, they were too difficult to store, the subjects had moved on or died, and the photo labs that printed them had long since shuttered.

Those that were not discarded or set alight were left to degrade in rice bags and cardboard boxes, the humid Lagos air slowly destroying the emulsion.

When Karl Ohiri, a British Nigerian artist, first heard about this, he was shocked.

“I was witnessing this history that was on the verge of being destroyed,” he told CNN.

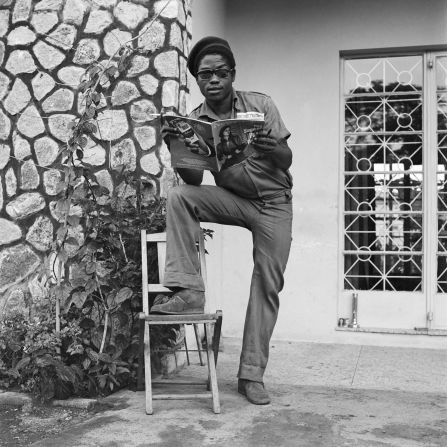

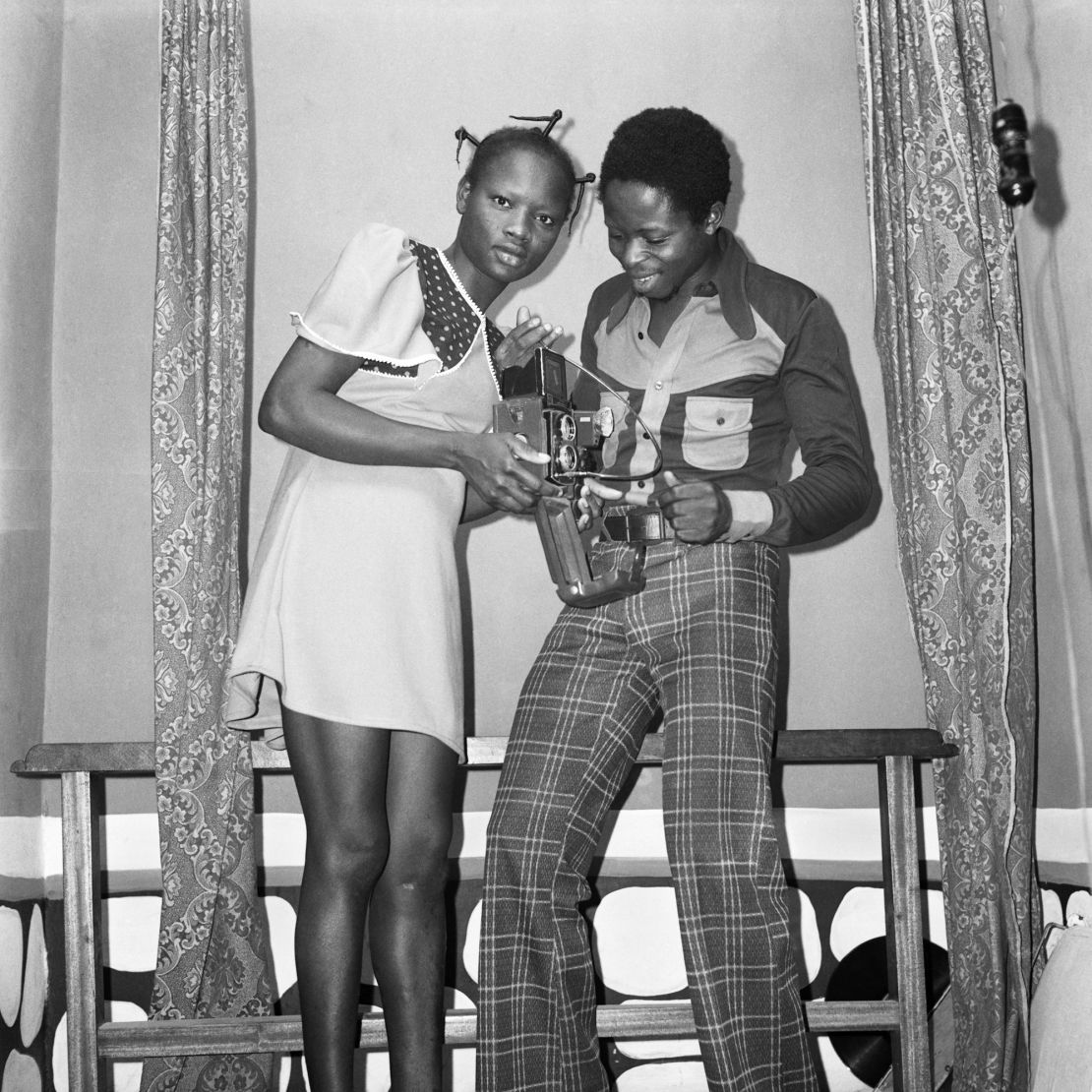

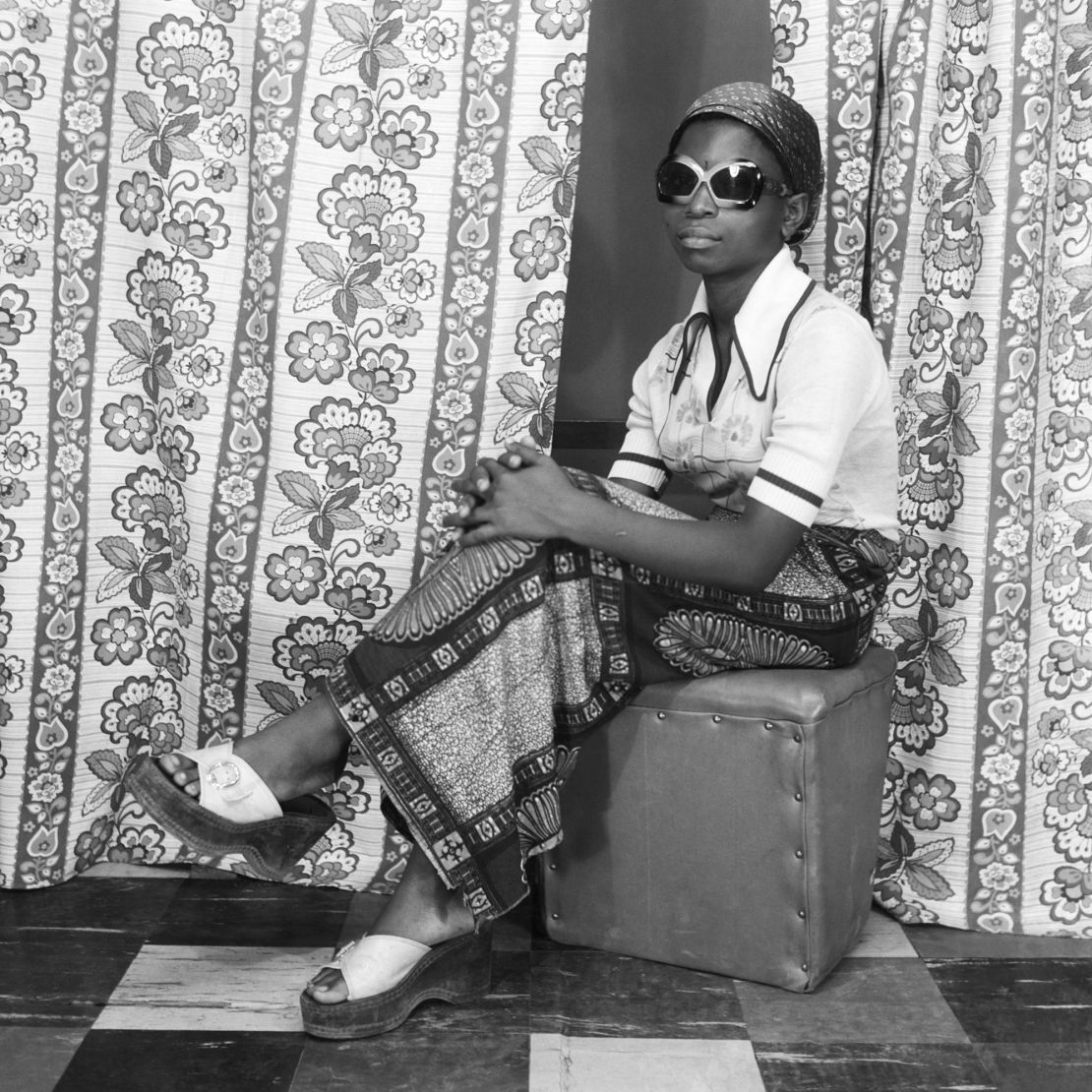

These analog photographers captured life in Lagos from the 1960s to the early 2000s.

From black and white portraits of young men in their bell bottoms, to a woman praying in front of a backdrop of the Islamic holy city of Mecca, to color photos of people showing off their new cassette players, the images these photographers made were a glimpse into Nigeria’s biggest city before the advent of digital photography.

However, they had never been digitized or archived — there were no backups.

In countries like the UK, Ohiri said, museums might have taken the photos, adding them to their vast archives; London’s V&A Museum has 800,000 photos in its collection and the National Portrait Gallery has 250,000.

But in Lagos, Ohiri explained, “there wasn’t anywhere to house them.”

Ohiri and his partner Riikka Kassinen launched Lagos Studio Archives to save the collections. They have spent the last nine years hunting down studios and photographers, cataloguing their archives, and creating exhibitions of the work.

It has not always been easy. “Lagos moves fast,” Kassinen explained; many of the photographers have since died, their studios torn down and new developments built in their place. There is sometimes so little trace of the studios that “it’s almost like (they) never happened,” said Ohiri.

Even if the pair could find the photographers, sometimes they were too late. “We’ve gotten to some photographers who had three or four decades of work that doesn’t exist anymore,” Ohiri said. “All of that history and heritage and there’s nothing left… it takes all of that time to amass, and just half a second to put some kerosene on it and light it up and that’s it. Just gone.”

Initially, many of the photographers did not understand their interest. “They just thought we were crazy,” Ohiri said. Now they have the work of at least 25 photographers in the archive, though they cannot be sure of an exact number as some of the troves they were given contained multiple photographers’ work.

Nor do they know how many negatives are in the collection, only that it is in the hundreds of thousands, piling up in Ohiri and Kassinen’s studio in Helsinki, Finland. “We might not be able to (digitize) everything in our lifetimes,” Ohiri conceded.

Theater of dreams

The ’70s was a period of rapid change in Nigeria. The country’s civil war had ended, Nigerian oil had boomed, and an increasingly urban population was enraptured by Fela Kuti’s Afrobeat. Photo studios became a place for people to document their everyday lives, show off their accomplishments and celebrate events. “It was a theater of dreams where people could really show their aspirations,” Ohiri said.

In the midst of these social and cultural changes sweeping through Lagos was Abi Morocco Photos.

Made up of husband-and-wife photographers John, who died in 2024, and Funmilayo Abe, Abi Morocco Photos worked from the early 1970s to 2006. First from a studio on Aina Street, and later moving, the pair took portraits at the studio, as well as visiting customers’ homes, attending events and ceremonies, and shooting portraits in the streets.

Ohiri and Kassinen recently curated an exhibition of the Abes’ work from the 1970s at the Autograph gallery in London, and have plans for a photobook of the couple’s work.

The show followed the archive’s inclusion in the New Photography Exhibition at New York’s MoMA, in 2023. “Archive of Becoming” was an experimental series of images, culled from damaged negatives. Ohiri and Kassinen had to wear masks to protect them from the fumes and mold that had grown on the discarded negatives as they painstakingly preserved them.

Now the archive is planning a project on female photographers and they want to make the overall collection accessible to citizens of the megacity through books and exhibitions.

Despite exhibiting the work around the world, the pair have never met any of the paying clients — the closest they have gotten is a friend who recognized their uncle in one of the pictures. They hope that people might one day recognize the scratched black and white portraits, the mold-stained faces, and time-faded colors, so that the thousands of negatives can become not just a document of the city, but “a family archive of Lagos.”