Some soldiers prove their valor in battle. Lt. Roland Christensen revealed his character on another proving ground—with a split-second decision that would change another Navy pilot’s life.

On March 17, 1947, Christensen gathered with other flight instructors at a naval air base in Glenview, Illinois. They appraised a group of nervous trainees who had assembled for the first day of selective flight training. The stakes were high — an average of 10 pilots per day washed out of Glenview.

One of the trainees had another reason for nerves. He was a slim, Black man named Jesse Leroy Brown. The son of Mississippi sharecroppers, Brown was attempting to become the Navy’s first Black pilot. One flight instructor told him “You’ll never sit your Black a** in a Navy plane.” Others dubbed him “oil slick” or called him “n***er.” The other instructors ignored Brown as they greeted trainees and peeled off for their first training flights.

But Christensen approached him with an outstretched hand.

“You’ll be flying with me today,” Christensen said, ignoring the snickers and glares from the other White trainers. Brown snapped to attention with a hearty, “Yessir!”

Brown would go on to break the Navy’s color barrier, becoming its first Black pilot. He would earn the Distinguished Flying Cross for valor during the Korean War. A Navy ship would eventually be named after him, and his life would inspire a bestselling book and movie.

But Brown never would have taken off without Christensen’s moral courage. These are the type of stories that have long helped make the modern US military so distinctive. The military is the most racially integrated institution in America. This is not just reflected in numbers but also in power: Although problems with deep-rooted racism persist, people of color have risen to the top echelons of the US military.

That integration, though, goes beyond race. The military is one of the few large institutions left in America where citizens voluntarily form close relationships with people of different religions, socio-economic backgrounds and ethnicities — all in service of a common national purpose.

Combat veterans in particular talk about the brotherhood, and sisterhood, formed in battle.

“The enduring emotion of war, when everything else has faded, is comradeship,” William Broyles Jr., a combat veteran in Vietnam, wrote in a classic essay. “A comrade in war is a man you can trust with anything, because you trust him with your life.”

But now some of America’s leaders are telling a different story. The Trump administration has launched a purge of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives throughout the armed forces and military academies. Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth says a culture of “wokeness and weakness” has made the military less lethal.

Hegseth, who wrote in a book published last year that “America’s white sons and daughters are walking away” from military service, says he wants to restore the “warrior” mentality to America’s military.

“I think the single dumbest phrase in military history is ‘Our diversity is our strength,” Hegseth said in February in a speech at the Pentagon.

But the strongest rebuttal to Hegseth’s argument is military history itself. Many of the nation’s biggest military blunders occurred because there wasn’t enough diversity in the armed forces.

How racism helped lead to a military disaster

Consider one the worst military disasters to befall the US: the Japanese’s navy’s 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, which triggered the nation’s entrance into World War II. Most history books describe the event simply as a Japanese sneak attack. At least 2,400 Americans were killed and images of the massive USS Arizona battleship, engulfed in flames and billowing black smoke, represent one of the nation’s most humiliating military failures.

But the US had ample warnings that the Japanese might attack. Why didn’t they heed those warnings?

One factor was racism, some military historians say.

America’s military leadership in the mid-20th century was all-White, and many commanders harbored stereotypes about the Japanese. When Admiral Husband Kimmel, commander of Pearl Harbor’s navy base, was later asked about the intelligence failures that led to the attack, he said, “I never thought those little yellow sons of bitches could pull off such an attack, so far from Japan.”

US military leaders had succumbed to “groupthink,” which often occurs when there’s not enough diversity in a decision-making body.

The term was popularized by psychologist Irving Janis. It comes from an essay he wrote in the 1970s that described how groupthink leads to military failures. It describes a dynamic where a group unwittingly creates a culture of conformity when making decisions. The desire for group consensus blocks out alternative points of view. No one feels empowered to disagree. The risk for groupthink increases with homogeneous groups, or groups with members who share the same background and experience.

Janis wrote that American military commanders didn’t pay attention to warnings of an impending attack in part because of groupthink. They saw Japan “as a midget that would not dare to strike a blow against a powerful giant.”

He also wrote that groupthink led to other American military blunders, including the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba under President Kennedy and President Truman’s ill-fated decision to invade North Korea, which brought China into the Korean War.

Groupthink also led to the debacle in Vietnam. The Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Barbara Tuchman wrote the US lost that war in part because the Kennedy and Johnson administrations lacked anyone with a deep understanding of Vietnamese culture, politics and history.

She had a term for that groupthink failure: “The March of Folly.”

With its DEI purge, the Trump administration is making the same mistake that American military leaders made in the past, says Kyle Bibby, an infantry captain in the US Marines who served in Afghanistan. He cited several recent decisions: Trump’s firing of Charles Q. Brown, the second Black person to serve as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (Colin Powell was the first); and Hegseth’s firing of Admiral Lisa Franchetti, the chief of the Navy.

The Defense Department has also banned using official resources to celebrate cultural awareness events such as Black History and Hispanic Heritage months. The US Naval Academy last month banned nearly 400 books in its library that dealt with racial justice, gender and LGBTQ+ issues. The library, however, reportedly still retained two copies of “Mein Kampf” by Adolf Hitler.

“They’re trying to make a very clear statement to the military that this is a White man’s military and the rest of you will fall in line,” says Bibby, co-founder of the Black Veterans Project, a group that preserves the legacy of Black veterans and secures restitution for Black soldiers denied benefits.

Bibby says the purge doesn’t make business sense, either.

“There’s no one on Earth who genuinely thinks that having differing opinions and experiences wile coming together to solve issues or build products is a bad thing for a team,” Bibby tells CNN. “The only people who think like that are people who believe in groupthink.”

Inclusive armies are more effective

Yet research shows it’s not enough for a military to be diverse. Numbers don’t mean much if women or non-White soldiers don’t feel valued and heard. This belief led to one of the most important victories in the Iraq War, one American general recently wrote in an essay.

Gen. Mark Hertling was commanding an Army division during the Iraq War in 2008 when he noticed an increase in suicide bombings carried out by Iraqi women, often in crowded public places. He couldn’t figure out how to stop it. Cultural prohibitions prevented men from touching and searching women.

The solution came from a junior female officer. At her suggestion, the military arranged a conference for Iraqi women to convince them that they had a stake in their country’s future. Within months, 60 female officers were fanning out across Iraqi provinces.

Would a woman officer feel comfortable approaching a male general with an out-of-the-box suggestion in today’s anti-woke culture?

Hertling, who is retired and a former CNN commentator, doesn’t answer that question in his essay, but he says that female officer saved lives.

“By the time 1st armored division rotated home, not only was the female suicide-vest cell almost completely destroyed, but the overall level of violence in northern Iraq was down significantly,” Hertling wrote.

The scenario Hertling described would not have possible not too long ago. This is not the US military’s first DEI purge. The voices and contributions of women and people of color were overlooked and erased through much of America’s military history.

Black soldiers were routinely treated as second-class citizens, held menial jobs such as cooks and were forced to serve in racially segregated units. Women in the military routinely experienced — and still do — discrimination and sexual harassment.

President Truman began to change this culture in 1948 when he issued an executive order desegregating the US military. Today, 32% of active-duty members are racial minorities and 17.7% are women, according to a 2023 Department of Defense study.

The military’s march to diversity faced some of its stiffest challenges in Vietnam. The racial tensions of 1960s America spilled over into the battlefield. There were constant reports of “fragging,” incidents in which US soldiers killed their comrades. Racial tensions between White and Black soldiers led to many fragging incidents.

The military created many of its diversity programs after Vietnam because they learned that a racially divided army cost lives, says Matthew Delmont, author of “Half-American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad.”

“It wasn’t about being politically correct,” Delmont says. “It was about we’re going to be less effective fighting wars if we can’t sort out this racial business.”

One Vietnam veteran recalls how racial tension affected his soldiers. Karl Marlantes, was then a young White man from a coastal logging town in Oregon when he commanded a platoon in Vietnam. He recalls the sensation of fighting two battles—one against the North Vietnamese, and another to hold marines together in the rear.

“I can just remember the sadness I felt in my platoon,” says Marlantes, who wrote about his war experiences in “Matterhorn,” and “What It Is Like to Go to War.” “We would all work together in the bush but when we got off the chopper, all the Black kids are in one part and the White kids in another part.”

Marlantes tells CNN he once tried to persuade a Black soldier to hang out with White soldiers as well but the soldier refused.

“He said I don’t want to be the one Black guy hanging out with a bunch of White guys when suddenly there’s a riot,” Marlantes says. “There was a lot of fear.”

That type of fear can lead to defeat. Armies that are divided by racial and ethnic tensions that bleed over from civilian life underperform, says Jason Lyall, author of “Divided Armies: Inequality and Battlefield Performance in Modern War.”

Lyall says he studied nearly 850 armies in 250 wars fought since 1800 and made a discovery: inclusive armies fight harder, suffer lower rates of desertion and exhibit more creative problem solving on the battlefield.

“Victory on the battlefield over the past 200 years has usually gone to the most inclusive armies,” Lyall wrote in a 2020 essay, “not the largest or best equipped.”

The DEI purge could hurt White soldiers, too

There was another reason the American military decided to become more diverse after World War II. They saw what happened to Nazi Germany.

People sometimes forget that Nazi Germany was built on, and destroyed by, racism. A racist demagogue persuaded Germans that other groups were inherently inferior. The Nazis’ demonization of ethnic and religious minorities, as well as political opponents, led to the Holocaust.

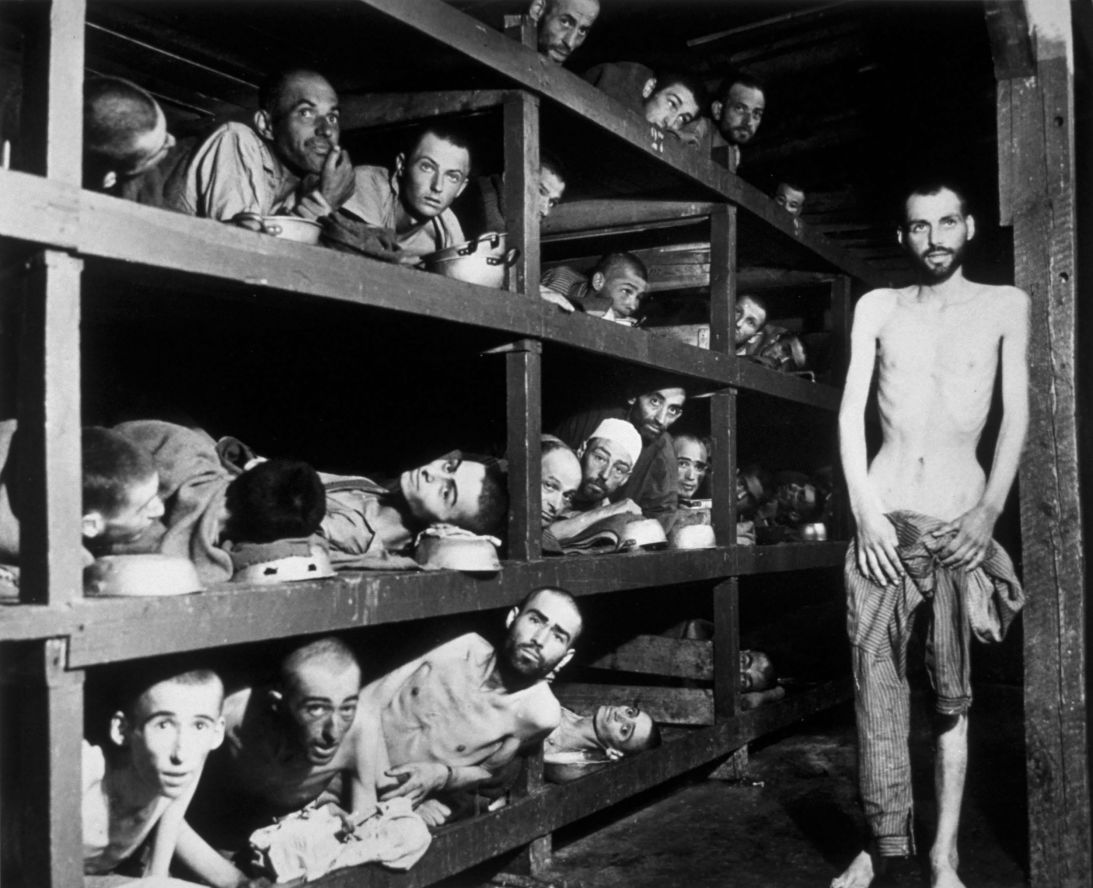

Many of the American soldiers who liberated the concentration camps were stunned that an advanced country like Germany could turn so barbaric. Some of them were Black veterans like Leon Bass, who simmered in anger over the racist treatment he received in the segregated Army. Then he entered the Buchenwald Concentration camp.

There he encountered what he called the “walking dead”— emaciated survivors who wordlessly stumbled toward him with sores across their naked bodies.

“Segregation, racism, can lead to the ultimate (horror) … that’s what I saw in Buchenwald,” says Bass, who died at 90 in 2015.

Fear of a similar democratic collapse motivated Americans like Bass after World War II. They resolved to, as the author David Brooks said, never “fall for the strongman’s deductive promise of domination.” They invoked, without irony, America’s traditional motto, “E Pluribus unum,” meaning “Out of many one.”

No other idea captured the nation’s imagination like racial integration during the 1950s and ‘60s, says Leonard Steinhorn, co-author of “By The Color Of Our Skin.”

“We saw ourselves as the big melting pot where everyone blended together and all the characteristics of different groups added to the pot,” Steinhorn tells CNN. “We wanted to believe that we could be better, that we weren’t bound by the prejudices, hatreds and outdated ideologies of old.”

But in recent years the desire for common ground seems to have evaporated. Our schools and communities remain widely segregated. Diversity programs are being driven out of academia and corporate America. People are self-sorting into political enclaves where they have little contact with people with different opinions.

The military is a last bastion of integration in America. Not even college and pro sports teams approach its commitment to the concept. Communities with large military installations dominate the list of the least segregated metropolitan areas of the US. There are higher rates of intermarriage among military members.

That diversity serves a vital military interest, some of the country’s leading military leaders recently said. Thirty-five retired senior defense officials, including four former chairmen of the joint chiefs of staff, signed an amicus brief in 2022 supporting diversity as vital for the nation’s armed services.

“History has shown that placing a diverse Armed Forces under the command of a homogeneous leadership is a recipe of internal resentment, discord, and violence,” they wrote.

That diversity is also needed more than ever because of another factor: In recent years the military has faced a severe recruiting shortage. The Army, for example, missed its recruitment goal by nearly 25% in 2022 and 2023. An uptick in recruiting that began last summer has carried over into 2025 so far. But a fundamental challenge remains: an all-volunteer force must consistently attract large numbers of people of color if it’s going to remain effective.

Here’s another intangible reason why diversity makes the military stronger. Some of the biggest beneficiaries of this diversity are White men. They may become hidden casualties in this war on wokeness.

Diversity not only increases the chance that they will succeed in war zones. It teaches them how to negotiate differences with someone who is different — a vital skill for preserving a multiracial and multicultural democracy.

Bibby says Black Marines swelled with pride when they saw his captain bars, but it was also important that White soldiers saw him. There are numerous historical examples of White soldiers who harbored racist attitudes being transformed by serving with, and fighting alongside, Black soldiers.

“We don’t talk enough about how much it means to young White men who have never seen a Black captain to understand that I’m a part of this damn story,” Bibby says. “It’s important that they see Black and women officers and they understand that we’re all part of the same team.”

Marlantes says he has a comfort level with Black people he probably wouldn’t have otherwise if not for his experiences in the Marines. He says he met all sorts of soldiers who expanded his perspective.

“We had an artillery forward observer whose great-grandfather owned Hilton Head,” says Marlantes of the popular South Carolina tourist destination. “He was rich. And he was in there with us, eating cold beans and being miserable while trying to save our ass by bringing in artillery.”

‘A bond that cannot be broken’

Christensen, the naval instructor who taught the Navy’s first Black pilot, was also transformed by an unlikely friendship. A descendent of Danish immigrants, he grew up on a Nebraska farm where he knew no Black people. But he was also poor and knew what it felt like to be an outsider.

He bonded with Brown over those shared experiences. The two men later exchanged letters that Christensen kept in a cedar chest in his home for more than 60 years.

Their friendship reflected the profound bonds that often form between people who serve together in the armed forces. “It is,” Philip Caputo wrote in his classic Vietnam War memoir, “A Rumor of War, “unlike marriage, a bond that cannot be broken by a word, by boredom or divorce, or by anything other than death.”

Their friendship ended when Brown was killed in action in 1950 during the Korean War. He was shot down and died before a rescue helicopter could ferry him to safety. After hearing about Brown’s death, Christensen became a helicopter rescue pilot and saved six pilots during the Korean War.

Before he died at 91 in 2014, he made an admission to his daughter, Nancy King.

“He told me that there wasn’t a single week that had gone by since 1950 that he didn’t think about Jesse Brown,” King said. “He said, “I dream about it.’ “

Critics of DEI will say that the friendship between Brown and Christensen fulfills their vision of a colorblind military. They want a military meritocracy, where only competence matters.

But integration of any kind never happens naturally in any large institution. The old hierarchies from civilian life can easily reassert themselves in the military. Armies splinter, groupthink leads to disasters and people die.

The Trump administration’s DEI purge ignores those hard-won lessons. It will go down as an epic case of friendly fire, a self-inflicted wound that harms more than helps.

It’s another march of folly.

John Blake is a CNN senior writer and author of the award-winning memoir, “More Than I Imagined: What a Black Man Discovered About the White Mother He Never Knew.”