CNN

—

For months, the tennis world has simmered with controversy in the wake of two doping cases involving top-ranking players: first, men’s player Jannik Sinner and months later, women’s player Iga Świątek.

And when the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) announced on February 15 that Sinner had accepted a three-month ban to settle his case and avoid it going to the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS), it thrust the issue back into the spotlight once again, particularly as the ban length means the Italian player won’t miss any grand slam tournaments.

“The anti-doping process is just all over the map, and it’s completely rogue,” Vasek Pospisil – a 2014 Wimbledon men’s doubles champion – told CNN Sport. “There’s absolutely no trust, that’s for sure.”

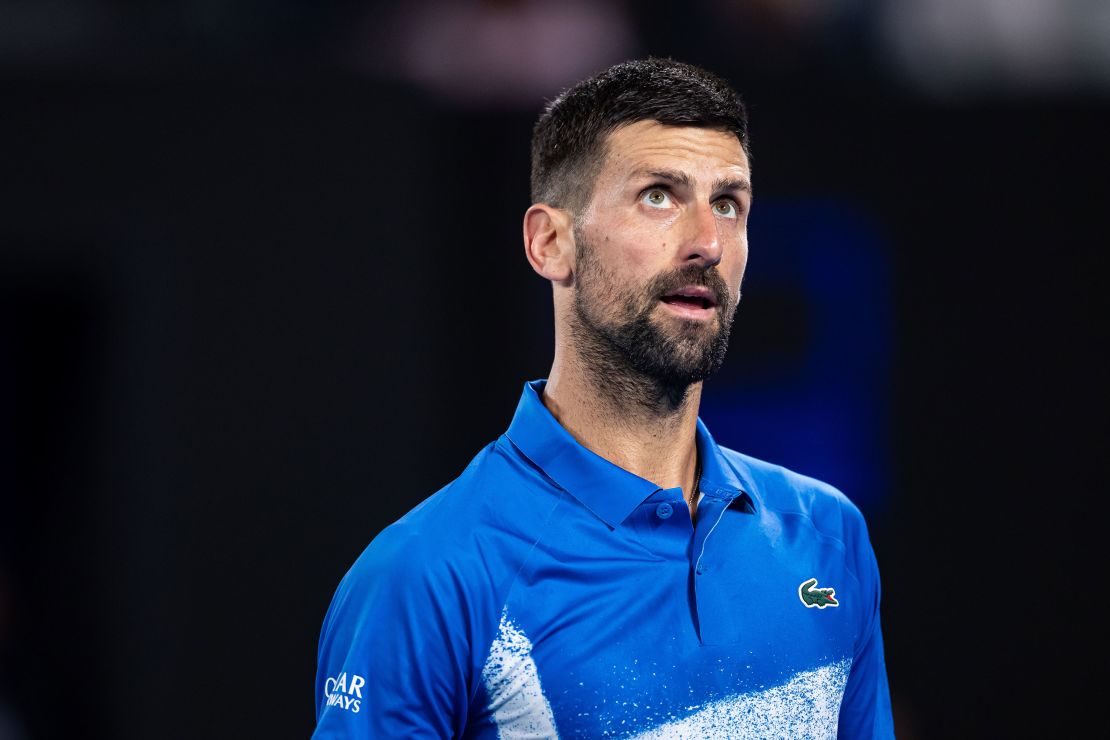

Pospisil and Novak Djokovic cofounded the Professional Tennis Players Association (PTPA), which acts as a players’ union.

Pospisil and several others say that the saga has exposed the different experiences of the anti-doping system felt by players – where the likes of Sinner and Świątek, who was banned for a month, have escaped with short sanctions and some lesser-known players have been hit with more severe punishments.

“The majority of the players don’t feel that it’s fair,” Djokovic told reporters at the Qatar Open. “The majority of the players feel like there is favoritism happening.”

But, for Marjolaine Viret – an associate professor at the University of Lausanne specializing in health and sport – these accusations of inequality are more “rooted in the legal complexity of the system, and the fact that broader audiences” don’t normally pick up on the differences between the cases.

Doping cases are inherently complicated, full of scientific and legal terms, and often take years to fully resolve as they wind their way through various courts and tribunals. Still, the outcomes in the Sinner and Świątek cases “did not seem particularly special,” she told CNN Sport.

Similarly, the fact that these cases were made public “is probably a healthy sign,” especially because they involve top players, said John WilIiam Devine, a senior lecturer in ethics and sport at the University of Swansea.

“You could look at these cases and say the system held in the sense that the tennis authorities … didn’t brush them under the carpet,” he told CNN.

Although the system seems to have held, there is a lingering perception among players that it has failed, revealing their lack of trust in the institutions, highlighting the financial inequalities among individual tennis players and spotlighting the issues with the way the current anti-doping system deals with contamination cases.

Players have directed much of their ire towards the International Tennis Integrity Agency (ITIA) which originally dealt with Sinner’s and Świątek’s cases. The ITIA maintains it approaches every doping case “in the same way, irrespective of a player’s ranking or status,” it told CNN in a statement.

Contamination as an excuse and a risk

Anti-doping works under the principle of strict liability, meaning that an athlete is automatically held responsible if a banned substance is found in their body and they have to prove how it got there.

“For an anti-doping rule violation to take place, the athlete doesn’t need to have intentionally doped,” Silvia Camporesi, a professor in ethics and sport at the KU Leuven university in Belgium, explained to CNN Sport.

A banned substance, even if it is unknowingly consumed in contaminated food or medicine, would leave an athlete liable and potentially facing sanctions. Both Sinner and Świątek say the banned substances entered their system in this way via contaminated products.

“Contamination is the most used excuse by cheaters, but this is also the risk faced by the (clean) athlete,” David Pavot, professor of sports law at the University of Sherbrooke in Canada, told CNN Sport.

Sinner twice tested positive for the banned substance clostebol in March last year and initially avoided suspension since an independent tribunal convened by the ITIA accepted his explanation that the anabolic steroid had entered his system via his physiotherapist, who had been applying an over-the-counter spray to his own skin – not Sinner’s – to treat a small cut.

Świątek’s case has some key differences to Sinner’s. She tested positive in August for trimetazidine, a type of heart medication normally used to prevent angina attacks. Unlike Sinner, she initially couldn’t explain how the drug had entered her system, and she missed three tournaments during her provisional month-long suspension.

Eventually, she explained the positive test by saying that a batch of melatonin she took to combat jet lag was contaminated by the banned substance – an explanation the ITIA accepted after testing the medication.

There are good reasons why the doping system is built on this principle of strict liability, even if it catches out some innocent athletes, added sports ethicist Devine.

As well as acting as a deterrent, it makes it easier for anti-doping authorities to sanction athletes who have doped.

“One of the most difficult things to prove in any kind of criminal or civil case is intent … by operating with that strict liability doctrine … it makes it easier for cash strapped sporting bodies to prosecute these cases,” Devine said.

Intent is considered later in the process, informing the length of the ban handed down to athletes, he added.

To defend themselves and prove they didn’t intend to consume these substances, both Sinner and Świątek would have marshalled their considerable financial resources. Sinner hired one of the best sports law firms in the world. Świątek’s team tracked down the batch of melatonin she had consumed.

In the end, Świątek received a one-month ban and Sinner a three-month ban. Neither of them missed any grand slam tournaments during this time.

By contrast, Pospisil said that in his role at the PTPA, he has seen many players “just take the ban because they can’t afford to pay for a lawyer, even if they are innocent.”

Articles picking over the fallout from these cases have drawn comparisons with other players – like Tara Moore, Stefano Battaglino and Simona Halep – who have faced much longer bans for seemingly similar positive tests.

Current world No. 231 Moore was provisionally banned in June 2022 after testing positive for banned substances. It took an independent tribunal 19 months to accept her explanation that she had consumed contaminated meat in Colombia, resulting in 19 months “of lost time, of my reputation, my ranking, my livelihood, slowly trickling away,” she wrote in a statement on X.

“I’m simply asking that everyone get the same treatment,” she said on X after Sinner’s three-month ban was announced. “I hope (Sinner’s) case will further improve the conditions in which players are treated and will be a precedent for future cases timeline.”

Then there is Italy’s Battaglino, who tested positive for clostebol in what he said were eerily similar circumstances to Sinner. But, unlike Sinner, he was banned for four years and described himself as a “pariah” in an interview with Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera.

As the then world No. 760, he had no access to his own physiotherapist like Sinner and would use those provided by tournaments. He says it was during one of these sessions that the clostebol entered his system.

“(Eventually,) only towards the end of the trials, after endless lack of answers from the tournament director, did they track down the physiotherapist who had accidentally contaminated me,” Battaglino told Corriere della Sera. The physio told him he always wore gloves and washed his hands, and an independent tribunal concluded that he couldn’t prove the source of his banned substance, and so there was no cause to reduce his four-year ban.

And there is two-time grand slam champion Halep, who was banned for four years after testing positive for the banned substance roxadustat. She released an impassioned statement in November, saying: “I stand and ask myself, why is there such a big difference in treatment and judgement?”

She always maintained her anti-doping violations were unintentional and, in March last year, CAS agreed and reduced the backdated ban to nine months, clearing her to return to the sport. She has since retired from tennis.

But in these cases, the players couldn’t prove the source of contamination as quickly as Sinner and Świątek could, meaning that their explanations weren’t accepted by the anti-doping authorities.

The ITIA, meanwhile, offered different comparisons. It directed CNN to the case involving Marco Bortolotti, the current world No. 109 in men’s doubles, who tested positive for clostebol in October 2023 but provided evidence of contamination and escaped a ban.

It also pointed to the case of Nikola Bartunkova, who was banned for six months after testing positive for trimetazidine which she later showed was caused by ingesting a contaminated supplement.

WADA told CNN it is “satisfied that justice has now been delivered” and acknowledged that “what the Sinner case highlights most of all is the issue of contamination.” The organization said that it has created a working group to provide expert advice on this issue and that its code has “adopted an increasingly flexible and tailored sanction regime that aims to impose appropriate consequences to reflect the nature of the anti-doping violation.”

Reinvention

For some, there is a sense that, to a certain extent, the anti-doping system needs “to reinvent itself,” said Viret of the University of Lausanne.

“First, deal with these contamination issues,” she said, “find a way to address this risk in the athletes’ environment that goes to the very limits of the duties of diligence that you can impose on athletes.”

Redirecting resources towards investigation instead of mass testing might prove more effective too, added Pavot, postulating that the actual prevalence rate of doping seems to greatly dwarf the proportion of positive tests recorded.

And when WADA updates its code in 2027, athletes judged to bear “no fault” for a positive test could receive a reprimand or up to a two-year ban.

Some players are also now calling for a complete overhaul of the sport’s anti-doping system.

“It’s a ripe time for us to really address the system because the system and the structure obviously doesn’t work for anti-doping,” said Djokovic. Meanwhile, American star Jessica Pegula said recently she doesn’t think “any of the players trust the process at all right now.”

While it’s unlikely that a complete overhaul will result from these cases, some changes have come out of it.

In January, the PTPA launched a program to provide pro-bono legal support to tennis players facing anti-doping violations. It was co-founded by Moore who said in a statement that “all players are entitled to due process – financial constraints or a lack of resources should never stand in the way of their rights.”

Whether a player who tests positive for a banned substance is guilty of doping, “that’s not for me to judge,” said Pospisil. “What I can judge is the fact that the system is just completely failed, it’s broken, and it needs reform.”