Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

CNN

—

The renovation of a football pitch in Austria’s capital has led to the discovery of a Roman mass grave housing the remains of more than a hundred soldiers who died in combat.

The construction company working on the sports field in the district of Simmering in Vienna found a large number of human remains at the site in late October, according to the Vienna Department of Urban Archaeology, part of the Wien Museum.

The remains of at least 129 individuals were uncovered during excavations by archaeologists and anthropologists from the museum and archaeological excavation company Novetus, the museum said in a press release Wednesday.

However, the total number of individuals is estimated to be more than 150, as the earlier construction works had displaced a large number of dislocated bones in the 16-foot-long pit.

The skeletal finds suggest “a hasty covering of the dead with earth,” as the individuals were not buried in an orderly fashion, but with their limbs intertwined with each other’s and with many lying on their stomachs or sides, the museum said.

‘Catastrophic’ military operation

After the skeletons were cleaned up and examined, researchers found that they were all male, and most were more than 1.7 meters tall (more than 5 feet 7 inches) and between the ages of 20 and 30 when they died.

Their dental health was generally good, with few signs of infection, but every individual analyzed bore injuries sustained at or near their time of death.

The variety of wounds, which were mainly found in the skull, pelvis and torso, and made by weapons including spears, daggers, swords and iron bolts, suggests they were sustained during battle rather than the result of execution – the punishment for military cowardice, the museum said.

“As the remains are purely male, it can be ruled out that the site of discovery was not connected with a military hospital or similar or that an epidemic was the cause of death. The injuries to the bones are clearly the result of combat,” it added.

The bones were dated to approximately 80 to 230 AD.

The men were probably robbed of their weapons, since only a small number of objects were found alongside them, according to the release.

Archaeologists uncovered two iron spearheads, one of which was found lodged in a hip bone.

Numerous hobnails were discovered near the feet of one individual. These nails would have studded the underside of leather Roman military shoes, the museum said.

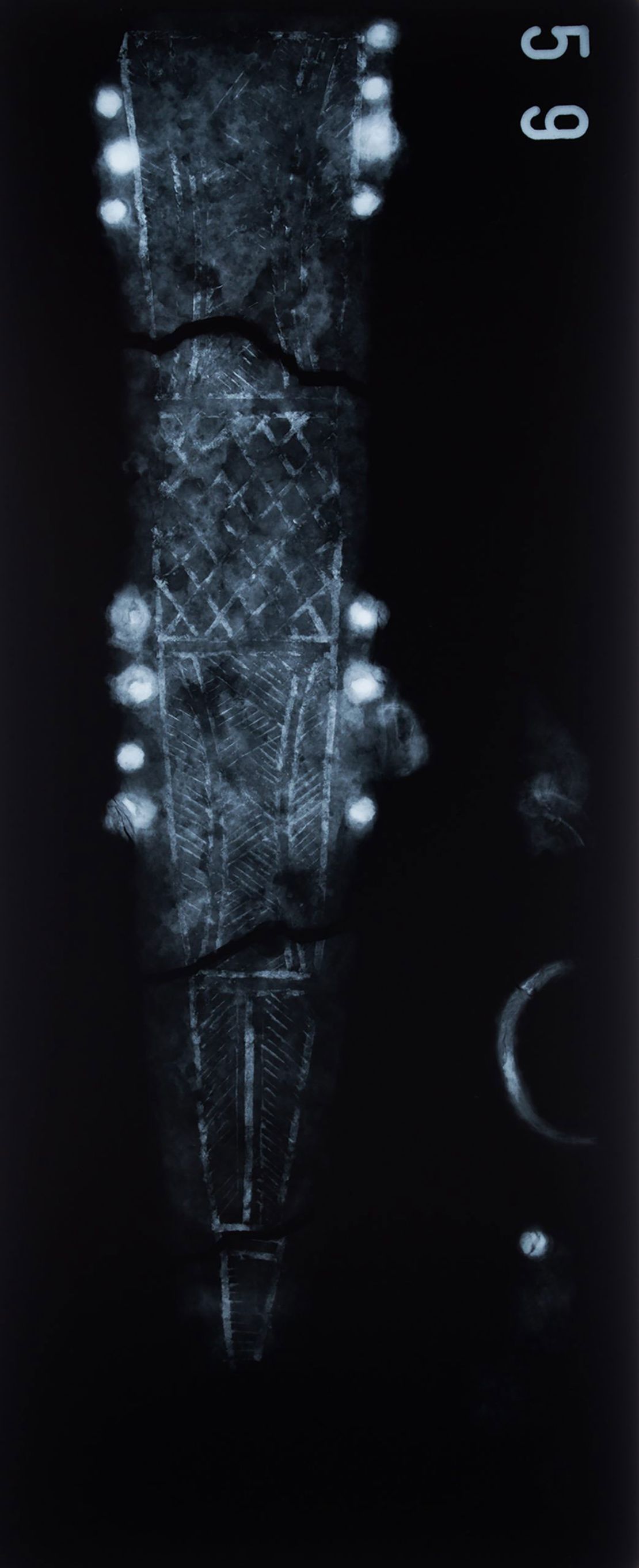

An X-ray of the scabbard of a rusted and corroded iron dagger revealed typical Roman decorations of inlays of silver wire. This was dated to between the mid-1st century and early 2nd century AD.

There were also several pieces of scale armor, which became customary around 100 AD, the museum said. However, they were unusual in having more square-shaped features than round, it added.

A cheek piece from a Roman helmet was found to be from a type that became customary from the middle of the 1st century.

“We are blown away by this find. It is a genuine game-changer,” Kristina Adler-Wölfl, head of the Vienna Department of Urban Archaeology, told CNN Friday, adding that this is “a once-in-a-lifetime discovery” for the museum’s archaeologists.

“There is archaeological evidence of Roman battlefields in Europe, but none from the 1st/2nd century CE with fully preserved skeletons,” she said.

Around 100 AD, ritualized cremation burials were common in the Roman-governed parts of Europe, with whole-body burials “an absolute exception,” according to the museum. “Finds of Roman skeletons from this period are therefore extremely rare,” it said.

“The undignified nature of the burial site along with the deadly wounds found on each individual suggests a catastrophic military confrontation, possibly followed by a hasty retreat,” Adler-Wölfl added.

Battle at the dawn of urban Vienna

Historical records show that in the late 1st century, during the reign of the emperor Domitian, costly battles took place on the Roman Empire’s northern Danube border between the Romans and Germanic tribes.

“This is the first time we have material evidence of the Germanic wars” fought by Domitian between 86 and 96 AD, Adler-Wölfl said. “Before the find, we knew about these conflicts only through some written sources.”

“Our preliminary investigation suggests with near certainty that the mass grave is the result of such a Roman-Germanic battle, one that likely took place in or around 92 CE,” she added.

The destruction of an entire legion is included in reports of disastrous defeats, which later led to the extension of the fortification line known as the Danube Limes under the emperor Trajan, according to the museum.

The Roman expansion of the town of Vindobona, which later became Vienna, “from a small military site to a full-scale legionary fortress occurred in that context,” said Adler-Wölfl.

“This would place the mass grave in immediate conjunction with the beginning of urban life in present-day Vienna,” she added.

The initial investigation by the team in Vienna will form part of a larger international research project, the museum said. This will include DNA analysis, to shed light on the lives of the soldiers and their living conditions.