CNN

—

Behind the red-bricked facade and marble friezes of the National Gallery of Denmark, visitors are now able to see nearly all of Michelangelo’s existing sculptures — the “most comprehensive” exhibition of his sculptural work assembled in 150 years according to the institution — and more than 1,000 miles away from where the majority of the Renaissance artist’s works are typically seen.

But to do so, the museum did not haul the 17-foot-tall David from the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence, or the unfinished figure called “The Genius of Victory” that sits nearby in the Palazzo Vecchio. Instead, “Michelangelo Imperfect,” hosted at the SMK (short for Statens Museum for Kunst), relies on some 40 reproductions, including a new set of 3D-printed copies made for the show by the Madrid-based studio Factum Arte.

Included is a 19th-century bronze version of “David,” plaster casts of the four famed allegorical figures seen on the tombs of the Medici Chapel, and 3D-printed and cast sculptures of Pope Julius II’s unfinished tomb. Though it’s not the first time a Michelangelo sculpture has been 3D printed — the University of Florence unveiled a David replica made of acrylic resin at the 2020 Dubai Expo — this time, the technology has been used to help bring together nearly all of the artist’s sculptural works in one place.

The show also features original works by the Italian artist, including 20 drawings and a group of maquettes — preliminary models in wax and clay.

“It is a bit of an experiment,” said Matthias Wivel, the show’s curator, in a video call with CNN. “It’s an exhibition that consists largely of reproductions.” Today, he added, “it’s not something you see so often.”

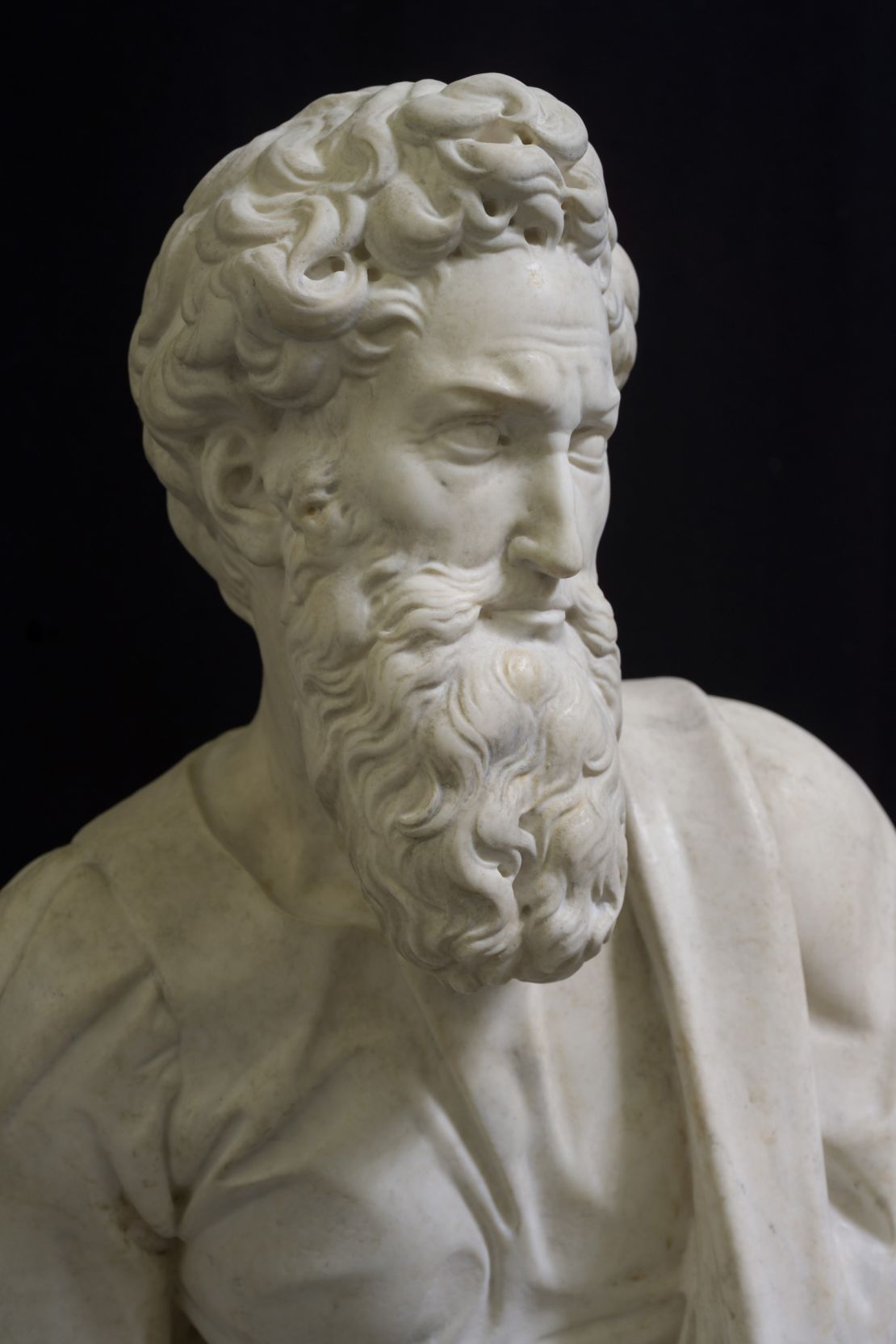

Michelangelo Buonarroti, the 15th-to-16th-century sculptor, painter and draftsman who has endured as one of the most famous artists of all time, is recognized for the dynamism and emotional qualities of his classical sculptures. They twist and turn in space, tense their muscles, or hold seemingly precarious poses despite being rendered in solid white Carrara marble.

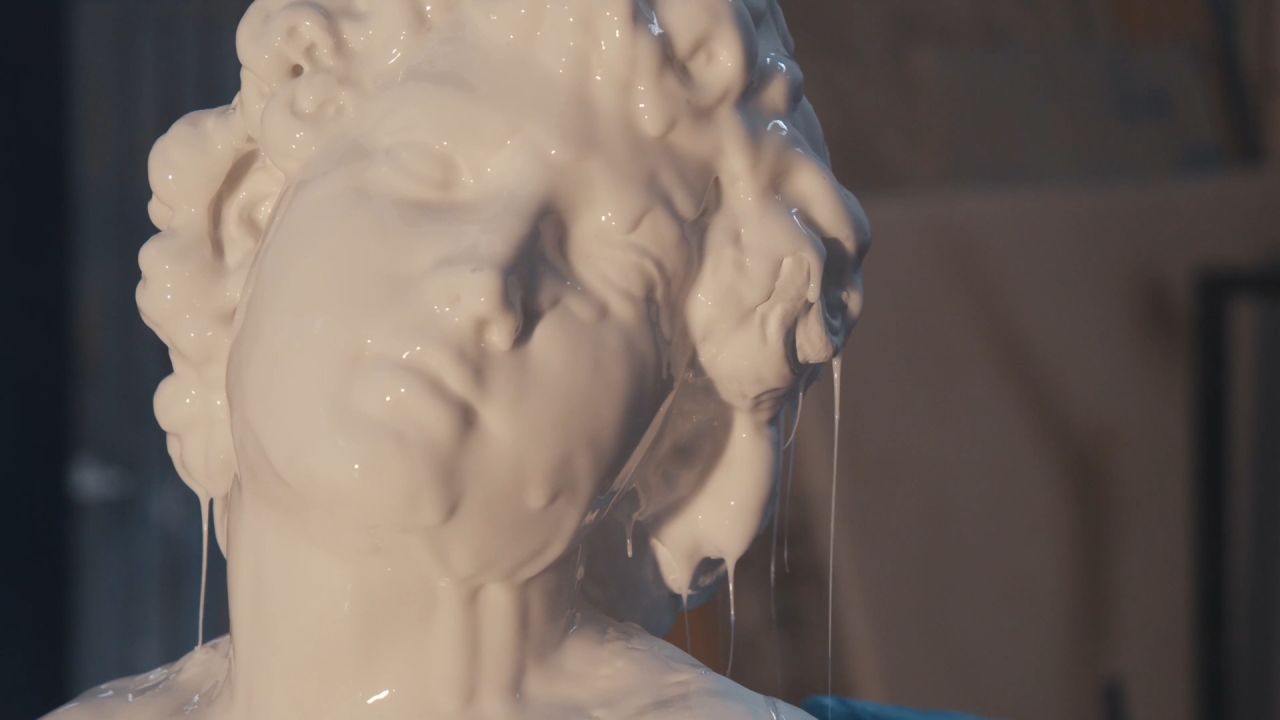

At Factum Arte’s studio, the team didn’t just 3D print each object, but used a mix of new and traditional techniques. The intensive process involved recording each work with photogrammetry and Lidar scanning to make a digital twin. They first printed each work in resin, similar to the “David” replica exhibited in Dubai, but they didn’t stop there. Then, they created silicone molds from the printed forms and cast each in a marble composite to get closer to the artist’s original material, before hand-finishing the final sculpture.

<div data-uri="cms.cnn.com/_components/video-resource/instances/cm904325t001i3b6mogjhswvk@published" data-component-name="video-resource" data-editable="settings" class="video-resource" data-fixed-ratio="16×9" data-parent-uri="cms.cnn.com/_components/video-resource/instances/cm9031d1r00003b6m60il63rp@published" data-video-id="me49525f773e9c3069b081284361433d0cbc5b1140" data-media-id="me49525f773e9c3069b081284361433d0cbc5b1140" data-live="" data-analytics-aggregate-events="true" data-custom-experience="" data-asset-type="hlsTs" data-auth-type="none" data-content-type="uploaded-clip" data-medium-env="" data-autostart="unmuted" data-show-ads="true" data-source="CNN" data-featured-video="true" data-headline="The studio making 3D-printed Michelangelo sculptures" data-has-video-player="true" data-description="<p>Art studio Factum Arte use state-of-the-art 3D-printing technology to create replicas of masterpieces by Michelangelo.</p>" data-duration="01:01" data-source-html='<span class="video-resource__source"> – Source:

<a target="_self" href="https://www.cnn.com/" class="video-resource__source-url">CNN</a>

</span>' data-fave-thumbnails='{"big": { "uri": "https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/videothumbnails/08913854-51017870-generated-thumbnail.jpg?c=16×9&q=h_540,w_960,c_fill" }, "small": { "uri": "https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/videothumbnails/08913854-51017870-generated-thumbnail.jpg?c=16×9&q=h_540,w_960,c_fill" } }' data-vr-video="false" data-show-html="” data-byline-html='<div

data-uri=”cms.cnn.com/_components/byline/instances/cm9031dbm00023b6m9i71tt2n@published”

data-component-name=”byline”

class=”byline vossi-byline”

data-editable=”settings”

>

</div>’ data-timestamp-html='<div

class=”timestamp vossi-timestamp”

data-uri=”cms.cnn.com/_components/timestamp/instances/cm9031dfm00033b6mtn3c31hk@published”

data-editable=”settings”

>

Published

2:56 AM EDT, Thu April 3, 2025

</div>’ data-check-event-based-preview=”” data-is-vertical-video-embed=”false” data-network-id=”” data-publish-date=”2025-04-02T15:43:22.606Z” data-video-section=”style” data-canonical-url=”” data-branding-key=”” data-video-slug=”michelangelo-replicas-3d-printing-factum-arte” data-first-publish-slug=”michelangelo-replicas-3d-printing-factum-arte” data-video-tags=”cprog,embed” data-breakpoints='{“video-resource–media-extra-large”: 660}’ data-display-video-cover=”true” data-details=””>

“Our goal is to make the (artworks) visually identical under exhibition conditions,” said Factum Arte’s founder Adam Lowe, in a video call with CNN. “You’re able to distinguish a difference if you can touch them or if you can tap them, because the temperature of the marble is not quite the same.”

Creating twins

But why exhibit replicas at all? And, if it really is virtually indistinguishable to the untrained eye (albeit a little warmer to the touch), is it Michelangelo enough?

Today, we might not assign much value to reproductions, but in the 19th century, plaster cast versions of famous sculptures were the stars of many museums. Institutions like the Art Institute of Chicago began their collections with plaster casts, and the Louvre’s plaster cast workshop, created in 1794, is still active today. Visitors who have traveled to Florence are already likely to have encountered a plaster doppelgänger of Michelangelo’s “David” in its original outdoor location at the Piazza della Signoria, but they have also been erected in London and Moscow, while bronze versions can be found internationally as well. Many were cast soon after the largest Michelangelo exhibition at the time took place in Florence in 1875 to mark the 400th anniversary of his birth, and featured a mix of original sculptures and new plaster duplicates, Wivel said.

But reproductions eventually fell out of favor, and eventually into disrepair, locked away in storage or destroyed. In 2004, the Metropolitan Museum of Art donated its once-prized collection to the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art. They had previously been neglected in “leaky” storage, The New York Times reported in 1987.

“It was a way of gathering and making accessible works of art that weren’t accessible to the general public, either because they were far away or because you couldn’t see them together,” Wivel explained. “There’s been this sort of fetishism of authenticity around original objects (beginning) in the 20th century.”

In fact, he added, the entire foundation for Western art would have been upended without reproductions, since precious few original sculptures from Ancient Greece still exist today; the vast majority of our knowledge of the period comes from Roman copies.

An ‘impossible’ show

The SMK’s extensive collection of plaster casts already included 27 out of around 45 existing Michelangelo sculptures, making it an ideal institution to host the show, Wivel noted. They were also able to relocate the bronze cast of “David” from 1896 — normally displayed outside in Copenhagen’s harbor district — indoors, becoming a “centerpiece” of the show. “I thought that was probably going to be impossible, but it happened,” Wivel said of moving the sculpture inside.

A show of this magnitude is “something you can only do with replicas,” Wivel said. “You get a richer experience of him as a sculptor by seeing it this way.”

To see the breadth of Michelangelo’s sculptures, you’d have to travel across Italy and make additional stops in cities around the world, including Bruges, London, New York and Paris. Most can’t move and some are behind bulletproof glass, such as the “Pietà” at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, or placed up high in cathedral niches, like four lesser-known saints he carved for a Siena chapel that until now, have never been reproduced. At the SMK, visitors will have unprecedented intimacy with nearly his entire sculptural output — though not quite all, as some institutions did not give permission to make copies, including two of the four unfinished nude prisoners Michelangelo carved for the tomb of Pope Julius II. (Those missing icons are “the great frustration of the show,” Wivel lamented.)

But all of the institutions who loaned the works will own the imaging and data that Factum Arte recorded, which — as they demonstrate through the exhibition — can be invaluable for conservation efforts. One of the most work-intensive replicas they made is a reconstruction of Michelangelo’s early sculpture of St. John the Baptist as an infant from 1495–96, which was housed in El Salvador chapel in Úbeda, but smashed during the Spanish Civil War. Conservators took 19 years to restore the work, which went back on view in 2015, but Factum Arte sought to improve upon it by scanning, printing, and casting each of the fragments before reassembling it.

“We spent two and a half years working on the reconstruction to put the fragments back as they might have been,” Lowe said.

Down to the details

Factum Arte’s data provides invaluable information for institutions, Wivel said. “Its accuracy is down to micron level… And that’s very useful in the future (for) conservation treatments. You can refer back and see what it was like at that time, especially if it’s damaged.”

The scans they capture are taken around 20 inches away from the works and “capture right down to the tiniest marks in the surface,” Lowe explained — even dirt and dust, which can prove challenging as it reads as extra volume or noise in the digital model.

The scans do have their limitations if parts of the sculptures are inaccessible, like the backs of some that are positioned in chapel niches. But the material and surface details mimic marble in a way that plaster can’t, Lowe emphasized, from the marble veining that’s meticulously added to match the original works, to adding dirt and cracks to the sandblasted exteriors to match the texture and condition.

In video clips of the studio taken by Factum Arte, monumental pieces of the sculpture sit together as they come to life over months and years. Spending that time with each work can profoundly change one’s impression of them, according to Sol Costales Doulton, the studio’s project manager who oversaw their making.

“The way you perceive these objects, it changes totally,” she said in the video call with Lowe. “The Genius of Victory” was one that began to subtly transform the more she spent time with it, she explained.

“Everybody saw him as a quite dispassionate, detached, idolized beauty. And then you start looking at him, and he starts gaining depth, and there’s actually something quite mysterious and deep in his eyesight, (like) something is calling him over his shoulder,” she recalled. “So the psychological charge that the sculpture expresses is totally different when you get a chance to be with it and listen to what it’s saying.”

Though it was a privileged position to have that length of time, she encourages visitors to take advantage of the proximity of the works together in one show, and really sit with them.

“So many times in passing through a gallery or a museum, you’re rushed to see all the masterpieces. Your attention span will be limited to a minute, a minute-and-a-half, and then you’ll move on to the next object,” she said. “So the possibility of being with them for months, they start to unravel many different narratives.”