Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by The Art Newspaper, an editorial partner of CNN Style.

CNN

—

Lorraine O’Grady, an indefatigable conceptual artist whose work critiqued definitions of identity, died in New York on Friday aged 90. Her gallery, Mariane Ibrahim, confirmed her death via email, adding that it was due to natural causes.

O’Grady became an artist comparatively late in life, when she was in her early 40s, and then worked for another two decades in relative obscurity before her work started coming to widespread attention in the early 2000s. She was included in the landmark 2007 exhibition “WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution” at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and the 2010 Whitney Biennial in New York. In 2021, the Brooklyn Museum hosted a major retrospective, “Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And.” For the occasion the artist, then in her late 80s, debuted a new performance art persona that involved her donning a full suit of armor.

“I thought that when I had the retrospective, there would be this great big moment when I would go into the galleries and see all of my work at the same time, in the same place, and have this big Aha!” she told New York Magazine in 2021. “The engagement of the audience, which involves a back-and-forth of question-and-answer, is the thing that was missing.”

Performance and back-and-forth questioning with an audience are hallmarks of the three projects O’Grady is arguably best known for — two under her own name, the other as a member of the anonymous feminist collective the Guerrilla Girls. In 1980, she premiered her most famous performance persona, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, a figure clad in a dress made from 180 pairs of white gloves, during an opening at Just Above Midtown, a non-profit gallery championing Black artists’ work. After handing out white chrysanthemums to those in attendance, she slipped on a pair of white gloves, whipped herself with a white cat-o’-nine-tails and, before leaving, shouted a poem that ended: “Black art must take more risks!!!” (She would reprise the role the following year during an opening at the New Museum in New York for an exhibition that she had not been invited to show in, though she had been asked to participate in its education programming.)

Then, in 1983, she entered a float into the annual African American Day Parade in Harlem. It featured a large, gilded and empty frame, and was accompanied by a troupe of 15 Black performers hired by O’Grady. Each one carried their own frame, holding them up in front of spectators lining the parade route, other performers and even — in one indelible image of O’Grady wielding her frame — a New York Police Department officer. Images from that project, “Art Is…” entered the wider lexicon of visual culture as O’Grady’s career gained momentum in recent decades. In late 2020, a video released by the Biden-Harris campaign celebrating its election victory reinterpreted the piece, with O’Grady’s blessing.

Boston beginnings

The child of Jamaican immigrants, O’Grady was born in Boston on September 21, 1934. Her identity was shaped both by her Caribbean heritage and her family’s anomalous class position. Her parents had been upper- and middle-class in Jamaica, but were confined to working-class jobs after they moved to the US. She did not fit naturally with either the predominantly White working-class community in Boston’s Back Bay, where she spent most of her childhood, or with Boston’s upper-middle-class African American elite.

“I always felt that nobody knew my story, but if there wasn’t room for my story, then it wasn’t my problem,” she told New York Magazine. “It was theirs.”

Before finding art, O’Grady tried many pursuits and careers, first opting to study Spanish literature at Wellesley College before changing tracks to study economics. After graduating she briefly worked for the Department of Labor before becoming a fiction writer. She enrolled in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa, but never finished her studies there. She moved to Chicago and worked for a translation agency before starting her own, completing projects for clients including Encyclopedia Britannica and Playboy. In the early 1970s she moved to New York City and became a rock music critic, writing for The Village Voice and Rolling Stone.

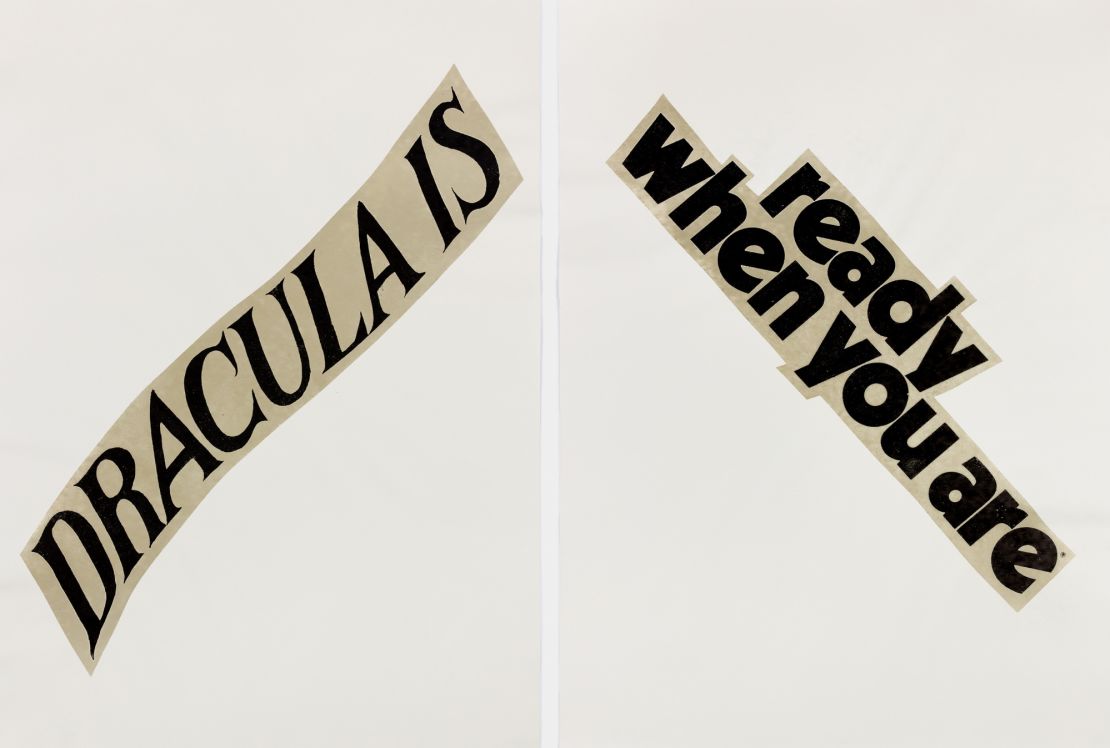

In the mid-1970s she started teaching literature at the School of Visual Art in New York. While cutting up an edition of The New York Times to make a gift, she began collaging together fragments of texts. These collages would become her first series, “Cutting Out the New York Times.”

“The problem I always had was that no matter who I was with or what I did, I got bored pretty quickly,” O’Grady told New York Magazine. “This was something I knew I would never get bored with, because how can I get bored? I would always be learning, and I would never, ever master it. That was part of the appeal.”

After that, though she continued to write — a book of her collected writings, edited by the scholar and critic Aruna D’Souza, was published by Duke University Press in 2020 — art-making became O’Grady’s primary activity. She also taught new generations of artists, taking on a full-time job at the University of California, Irvine, in the early 2000s.

“I don’t think the average person who becomes an artist starts off thinking of it as anything other than self-expression,” O’Grady told the Brooklyn Rail in 2016. “That gets educated out of them gradually. ‘Self-expression’ is something that gets tamped down in graduate school in particular — teaching at UC Irvine, I watched people struggling against that, against having to learn how to fit into the market. I don’t know that the nature of art itself has changed; I do think the idea of an ‘art career’ has changed.”

Defying the conventional ideas of an art career until the end, O’Grady had been busier than ever in recent years. Last year she left her longtime dealer Alexander Gray to join Mariane Ibrahim, a Chicago-based gallery with locations in Mexico City and Paris. At the time of her death, she was working on her first solo show with the gallery, at its French space, scheduled for spring 2025.

“Lorraine O’Grady was a force to be reckoned with,” Ibrahim said in a statement. “Lorraine refused to be labeled or limited, embracing the multiplicity of history that reflected her identity and life’s journey. Lorraine paved a path for artists and women artists of color, to forge critical and confident pathways between art and forms of writing.”

This past April, O’Grady won a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship, which was to support a new performance art piece reviving an old character from her past work. And while the reception for her art changed drastically over the years, the work itself maintained an intellectual rigor, criticality and playfulness that spanned her performances, collages, photographic diptychs and series, writings and more.

“I’m old-fashioned. I think art’s first goal is to remind us that we are human, whatever that is,” she told the Brooklyn Rail. “I suppose the politics in my art could be to remind us that we are all human. Art doesn’t change that much, actually. I’ve read lots of poetry from Ancient Egypt and Ancient Rome and they talk about the same things poets do today. Is anyone more down and dirty and at the same time more introspective than Catullus?”

Read more stories from The Art Newspaper here.