London

CNN

—

Amoako Boafo is in a buoyant mood. The 40-year-old Ghanian painter is about to open his first London show, “I Do Not Come to You by Chance,” at a UK outpost of the American mega-gallery, Gagosian.

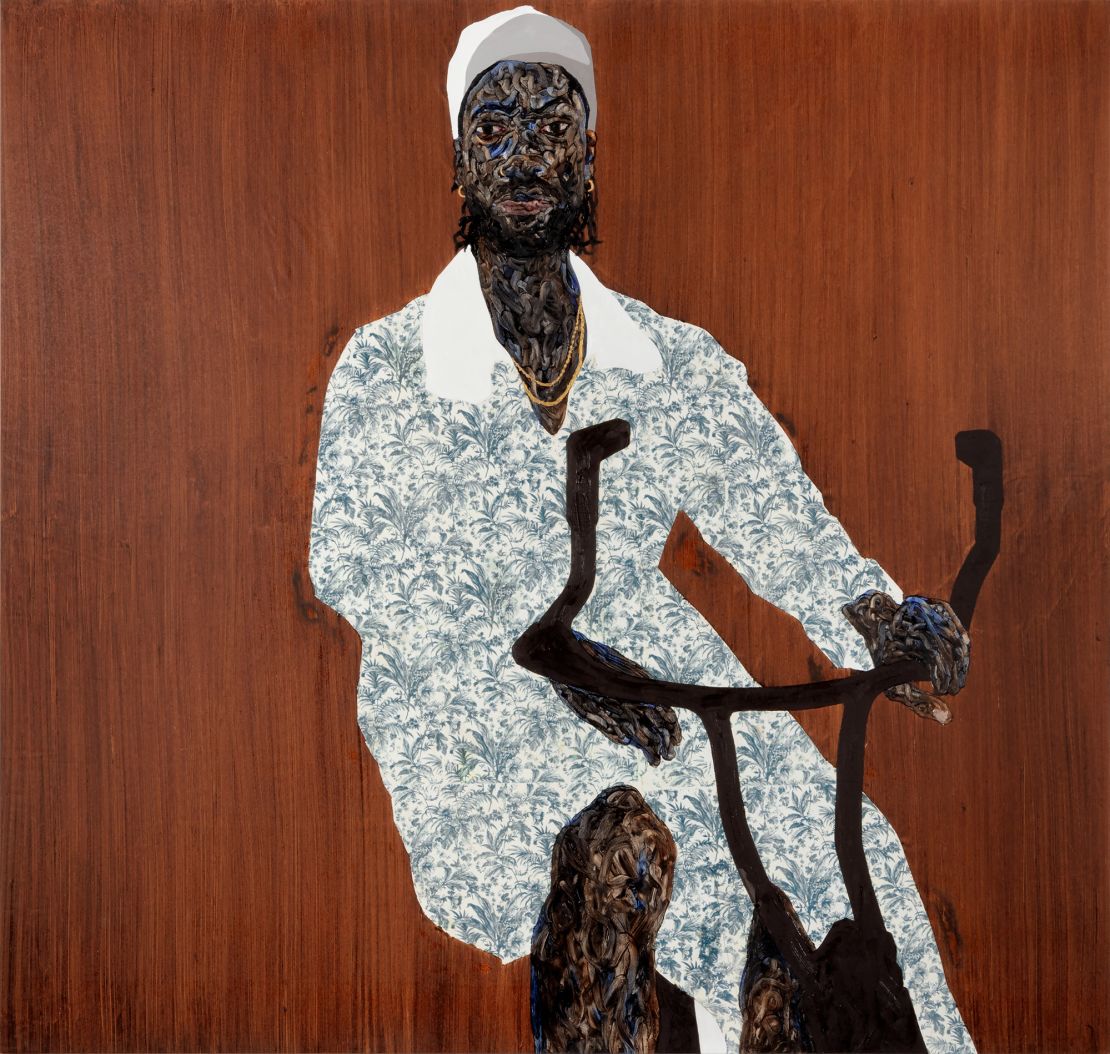

It’s an exhibition showcasing a new body of figurative paintings –– joyful, empowering portrayals of Black men and women, wrought in his distinctive lionized style and pairing fingertip-painting with paper-transferred patterns and blocks of color. In one, a woman stands, hands on hips, draped in white lace; another depicts Boafa himself, on a bicycle, clad in gold chains and chintz. Eshewing a conventional “white-cube” gallery setting, sections of the space are covered in patterned wallpaper. More strikingly, one room is filled with a life-size recreation of the courtyard at Boafo’s childhood home in Ghana’s capital, Accra.

“The idea of bringing the courtyard situation to London is me bringing home with me,” said Boafo over Zoom. “The courtyard is a space where I got to learn about almost everything: how to take a bath, how to take care of yourself,; how to sit quietly and listen, how to be disciplined.”

Boafo’s rise to art-world stardom has been swift and significant. In 2018, as he was finishing a Master of Fine Arts degree at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna in Austria, American artist Kehinde Wiley found his art on Instagram. “He suggested my work to his galleries,” said Boafo, “which was when things started picking up.” By December 2021, one of his paintings, “Hands Up,” had sold for over 26 million Hong Kong dollars ($3.4 mililon) at Christie’s, setting an auction record for his work.

Along the way, there was a residency at the Rubell Museum in Miami, owned by renowned collectors Don and Mera Rubell. Boafo signed with galleries in Los Angeles (Roberts Projects) and Chicago (Mariane Ibrahim). “Then Dior happened,” he said, referencing his collaboration with the French fashion house on its Spring-/Summer 2021 menswear collection, “and it didn’t slow down.” Three of Boafo’s paintings were even sent into space –– on exterior panels of a Blue Origin rocket. “I realized that maybe (my career is) never going to slow down –– and it never did.”

Unexpected learnings

Boafo was born in Accra in 1984; his father died when he was young and he was raised by his mother, who worked as home help, cooking and cleaning for different families. He developed a childhood love of art. “It was one of the ways that kids in the community got together: to draw,” he recalled. “I had always wanted to go to art school but, because of financial difficulties, I did not manage to.” Instead, Boafo ended up on the tennis court and played semi-professionally for several years, until a man Boafo’s mother worked for offered to pay his first tuition fees for Ghanatta College of Art and Design in Accra.

The four-year course taught him to draw and to paint. But he also took lessons from the tennis court: “not to sit idle; whatever happens, you move,” said Boafo. He moved to Vienna, went back to school and developed the painterly “language” that has since made global waves.

“He was confronting the ideology that art history has to be within a Eurocentric form,” said French-Somali gallerist Mariane Ibrahim, who supports emerging artists of African descent across galleries in Chicago, Mexico and Paris. “To purposely deconstruct traditional portraiture and figuration was really an act of rebellion, but also an act of making and creating your own history. I felt a connection in our experiences: being away from home in a place that doesn’t have much of an African- diaspora community.”

Today Boafo sits front and center of an art-world reappreciation of Black figuration. “He’s the head of a locomotive of a new generation of painters from West Africa and beyond,” said Ibrahim. The subjects of his paintings are his friends and family, and, frequently, himself, because, Boafo said, “I don’t see why I should not be present when I am representing my people.”

Impact beyond art

The paintings are a visual representation of Boafo’s desire to slow down and take stock. He hopes to work on one more exhibition with a similar theme in a different location –– “and then I will step away from making paintings for shows,” he said, continuing to explain that “I want to take a bit of break because I have other projects that I am passionate about –– like architecture and tennis. I want to build my own tennis academy, to develop (sports initiatives) so that the youth have something to do.”

At Gagosian in London, the new self-portraits –– including one of his largest paintings to date, in which Boafo reclines on a bed, swathed in floral patterns and surrounded by plants –– have an added poignancy. They act as “a reminder of the things that I want to do,” he said. “It’s a reminder to take a break and do yoga. Take a break and go on a bike ride. Take a break and look pretty and beautiful. Take a break and, sometimes, just stay home and relax.”

With his work now held in major museum collections, from London’s Tate and the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris to New York’s Guggenheim and the Hirshhorn in Washington, D.C., Boafo has become something of a local celebrity in Accra. “Sometimes you wake up in the morning and you have 10, 15 people at your door waiting to talk to you,” he said. “Everybody wants to put their problems in front of you. There’s some joy (in it) and there’s some stress.”

He is enmeshed in the local community through his dot.ateliers initiative — an artists’ residency, launched in 2022, that has since expanded to host writers and curators. Crucially, it offers spaces that foster experimentation and allow participants “to evolve or think on (their) own”, he said, adding: “I imagine dot.ateliers to be an institution which should live beyond me.”

Working alongside other creatives is key to Boafo’s practice. He frequently collaborates with Glenn DeRoché, the architect behind the courtyard constructed in London, a sculptural installation that also houses some of Boafo’s paintings.

“It was the perfect opportunity to pair what we both enjoy: working within communities, but also storytelling through what we create,” said DeRoché, sitting in the middle of the reimagined Accra courtyard, which has been reinterpreted and abstracted in a charred black timber structure. “I thought it was a beautiful way to start the show, with the seed of Amoako’s creativity, his ancestral birth home, but also to tell a story about community.”

Boafo may soon be shifting his creative focus, but the act of painting is a constant. “I’m always going to paint,” he said. “It makes me feel good. I will not be making paintings for gallery exhibitions. I’m just going to be painting for myself, to keep reminding myself of where I am and where I want to be –– you know, taking care of me.”

“I Do Not Come to You by Chance,” at Gagosian in Grosvenor Hill, London, is showing from April 10 to May 24, 2025.