CNN

—

A World War II-era plane is set to fly over a veteran’s funeral Saturday. Eighty years ago, elite paratroopers were leaping out of similar aircraft on a secret mission called Operation Firefly.

They jumped into burning wildfires, often landing in trees and having to rappel down ropes. When the ropes were too short, they fell to the ground, learning how to protect their bodies as best as they could.

Their job was to put out the flames caused by balloon bombs that Japan floated across the Pacific Ocean – the first recorded intercontinental weapons.

The paratroopers were highly trained and effective, making 1,200 jumps with the loss of only one man. And they were all Black.

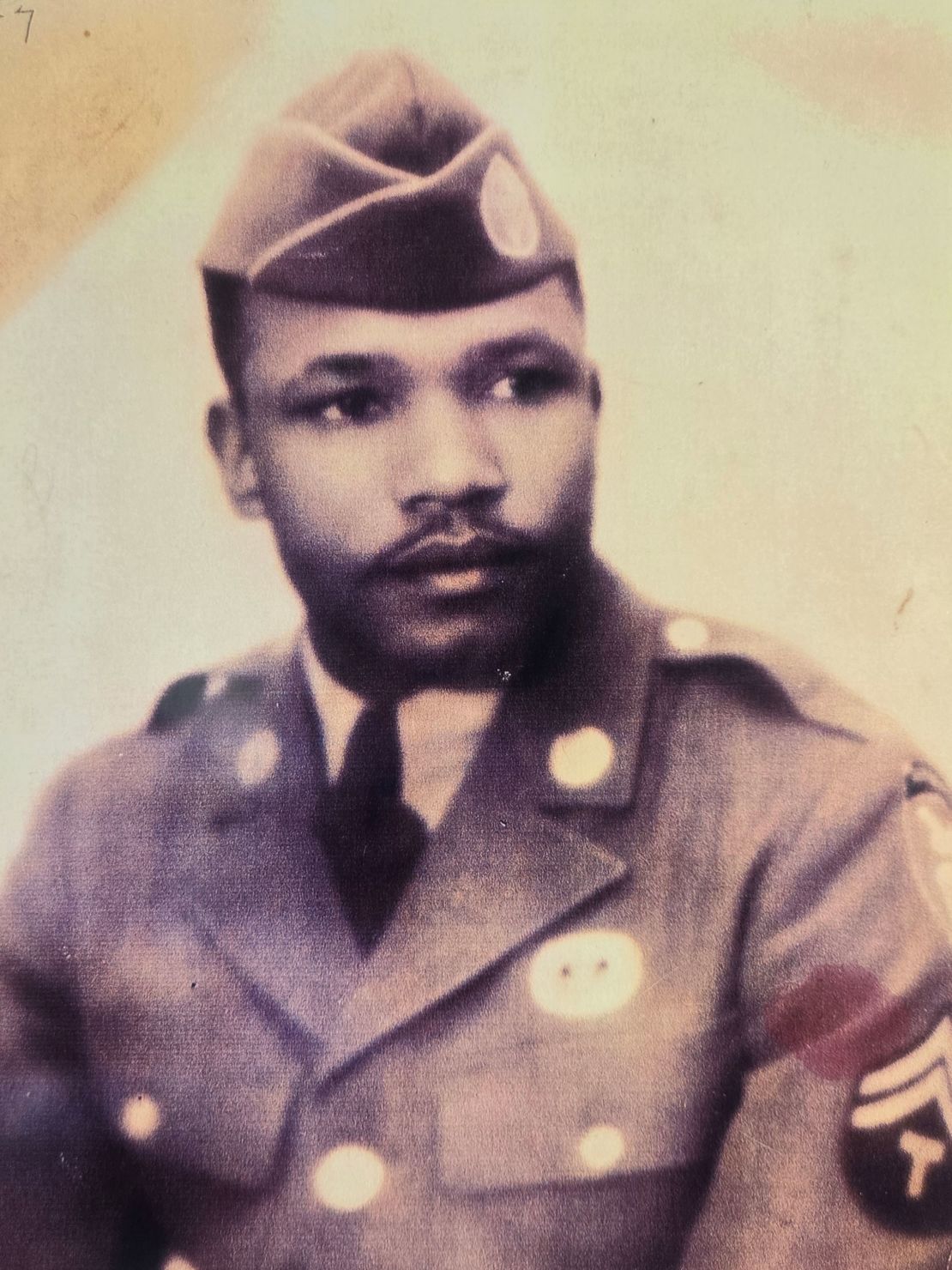

Sgt. Joe Harris, who is being laid to rest on Saturday, was one of them. He died last month in Los Angeles at the age of 108, perhaps one of the last of the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion known as the “Triple Nickles.”

“He broke barriers, he defied limits, and he proved that bravery knows no color,” Harris’ grandson Ashton Pittman told CNN.

Few knew about the Triple Nickles in their day and Pittman said he was unaware of his grandfather’s wartime heroism until he was a teenager.

“His (wartime) service was just a chapter in a long, extraordinary life,” added Pittman. “But it’s a testament to his resilience and his honor and his unwavering dedication to something greater than himself.”

Fighting a different kind of enemy

Even well into World War II, Black soldiers were typically relegated to menial, non-combat positions in the Army. They cooked, patched roads, did the laundry and guarded the military gates, according to Robert Bartlett, a veteran, retired college professor and Triple Nickles historian.

But 16 soldiers from the segregated 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion became the first Black men to graduate from the Army’s elite Airborne School at Fort Benning, Georgia. Their unit was nicknamed the “Triple Nickles,” referencing the members’ past as “Buffalo Soldiers” of the 92nd Infantry Division and the “buffalo” nickel of the era, though using the unusual spelling of nickle.

When the Triple Nickles finally received orders for a secret mission, they thought they would be heading to Europe to fight, Bartlett said.

Instead, their group, now 300 strong, was ordered to Pendleton Army Airfield in Oregon where they learned they would be taking on a different kind of enemy, one they had not trained for: Fires.

The Army was determined to keep “Operation Firefly” a secret, Bartlett said.

“They didn’t want the American people to panic that they were getting bombed by the Japanese, and they didn’t want the Japanese to know that they were successful,” he added.

“It was a secret war that the US was fighting.”

As the US Army was training the Triple Nickles to disarm bombs, the men were also being taught by the US Forest Service to become the first military smokejumpers.

“The military is going to train you how to deal with these bombs, but we’re going to have to train you how to jump into the mountains with picks and shovels and put out fires,” Bartlett recounted of what the Triple Nickles were told by the Forest Service.

Instead of the usual Army attire, the Triple Nickles were issued modified uniforms that were fire resistant, helmets with wire cages to protect from the thick brush, and ropes to lower themselves down from trees.

The precision, tactics and techniques developed and used by the Triple Nickles helped to create strategies for jumping with a parachute into wildfires. They also became experts in getting rid of explosives.

Harris completed 72 jumps during his time with the Triple Nickles. He was honorably discharged after he was seriously injured on a jump when his parachute failed to inflate fully.

Unknown then, hidden again now?

The Black heroes of the 555th did participate with their White brothers-in-arms for the 1946 victory parade in New York City even before the Army and the rest of the military was desegregated.

But they still had to sit at the back of the bus and endure the other hostilities of discrimination.

“It’s like ‘We don’t really respect you, but we need you,’” said Pittman of what his grandfather and others went through.

To historian Bartlett, the patriotism of the Triple Nickles was clear.

“These men loved their country. They loved their country, but their country did not love them,” he said.

“They saw their participation in the war as their duty,” he added. “It was what you were supposed to do.”

Bartlett said one reason why the Triple Nickles are not better known is because its members did not talk about their service much.

Omar Bradley, who’d later become mayor of Compton, California, grew up next door to Harris, and said he knew he’d been part of something special.

“It’s very difficult to understand jumping into a fire,” he said. “So, what it took to transform into that kind of man is something they didn’t talk about. But yes, we knew that Mr. Harris was a member of a very elite group.”

Some of the official recognition of the 555th is being lost. A page on the US Forest Service website about the agency’s connection to the Black paratroopers entitled “The Triple Nickles: A history of service, an enduring legacy” is now blank except for the message “You are not authorized to access this page.”

There has also been a purge of Pentagon websites under the Trump administration to remove content related to diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) that wiped the stories of baseball legend Jackie Robinson, who served during World War II, and the Navajo Code Talkers before they were restored amid public outcry.

Finally, recognized as a hero

After he left the Army, Joe Harris spent decades working as a border patrol officer, according to his grandson Pittman.

The younger man said he has grown more appreciative of some of the things his grandfather gave to him, like his Triple Nickles patch and his World War II jacket. “It means the world to me. It’s a piece of history, but it’s a piece of our family’s history,” Pittman said.

In October to honor his grandfather, he decided to go through paratrooper training, even though he is not in the military.

“I felt that I needed to do it to pay respect to him and to people that have served, especially the Triple Nickles,” Pittman said. In the future he hopes to travel and take part on jump teams to show his appreciation for veterans.

The World War II nonprofit Beyond the Call recognized Harris’ life. “Joe Harris’ bravery and selflessness exemplify the spirit of the Triple Nickle Paratroopers,” it said. “His remarkable story serves as a reminder of the sacrifices made by those who served during World War II and the importance of honoring their legacy for future generations.”

That legacy was to be honored Saturday, with a full military funeral complete with the fly-past.

CNN’s Dianne Gallagher contributed to this story.