Editor’s Note: Watch the final two chapters of the four-part CNN Original Series, “Lockerbie: The Bombing of Pan Am 103,” tonight at 9pm ET/PT on CNN.

CNN

—

Suse Lowenstein was working on a sculpture in her home studio in New Jersey when she received a phone call that would forever shatter her family.

It came from a friend. In a trembling voice, she asked Lowenstein which flight her son, Alexander, was on from his semester studying abroad in London.

“Pan Am Flight 103,” Lowenstein said.

Her friend let out a piercing scream.

“Haven’t you heard?” she cried.

It was four days before Christmas in 1988. Lowenstein listened in shock and horror as her friend told her the unthinkable: The plane Alexander was on had exploded in the sky over Lockerbie, Scotland, less than 40 minutes after takeoff.

Shattered, Lowenstein crumpled to the ground of her studio in Mendham Township, whispering, “no, no.”

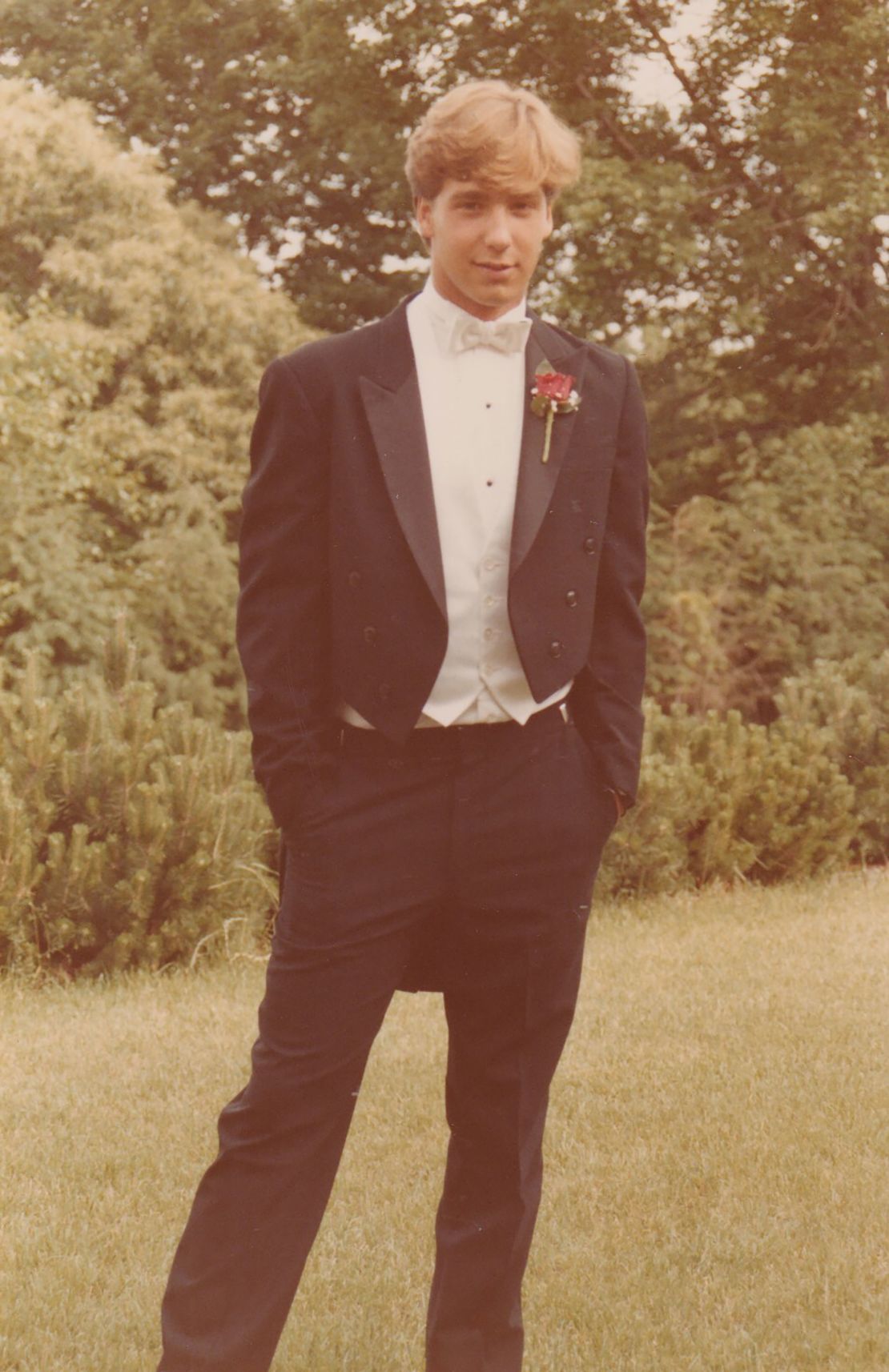

She later learned that Alexander was among 270 people killed when a terrorist’s bomb tore the plane apart. He was 21, and one of 35 Syracuse University students aboard the flight.

The plane crash killed 190 Americans in what was the deadliest terror attack on US civilians before September 11, 2001. A Libyan terrorist was convicted of the bombing and sentenced to life in prison. Authorities are still pursuing other suspects.

The tragedy was back in the news last month when President Donald Trump gutted a citizens advisory committee established by Congress to examine aviation safety issues after the Pan Am 103 bombing.

And nearly four decades later, the grief remains woven throughout Lowenstein’s life. As an artist, she’s grappled with it the only way she knows how: by making art.

As part of her healing journey, Lowenstein spent years creating a massive sculptural installation showing the raw emotion of 76 women who lost loved ones that day. The artwork, titled Dark Elegy, captures their expressions of pain, grief and rage the moment they heard the news.

It started as a tribute to those who lost children on the flight but has evolved into a symbol of all grieving women, she says.

“You never forget that instant in which you are told. The exact feeling, the posture of your body. It is what is depicted in Dark Elegy,” she says. “When your child is murdered, that grieving process never ends. In my case, I made it part of who I am and part of me. It’s inside of me. I live with it. I go with it. I make it mine.”

Before the attack, she had an ‘incredible need’ to see her son

Lowenstein still wears the bright red jacket her son had on when he boarded the flight. It hangs in her home studio in Montauk, New York, scarred by burn holes and rips from the crash. The letter “A” for Alexander, scribbled on the care label, is still visible.

As the oldest of two children, Alexander was time-conscious and punctual. With no cell phones at the time, her husband, Peter Lowenstein, held on to hope that their son had missed his flight and had no way to notify them.

But Suse Lowenstein says she knew her son would never fail to get to the airport on time, and she knew he was gone the moment she received the phone call. Officials released a passenger list days later, confirming their worst fears.

Alexander was an English major at Syracuse University and had been in London for the fall semester. Two weeks before his death, his mother flew to London to spend time with him. They traveled to her native Germany, where Alexander met some of his cousins and extended relatives for the first time, she says.

“I was overcome with this incredible need to go over to London and be with him,” Lowenstein says. “I couldn’t explain the feeling and it didn’t make any sense, but I did it and I got to spend a magnificent week with him.”

In the wake of his death, her overwhelming urge to visit her son that month suddenly made sense, she says.

The Lowensteins struggled to process their loss. Alexander’s only sibling, younger brother Lucas, had attended Syracuse with him and was deeply affected by their last conversation. At the time, the brothers were not getting along due to what Lucas describes as typical sibling squabbles.

“The last thing we said to one another was that we hated one another, but obviously that was not accurate,” says Lucas Lowenstein, now 56. “We loved one another. It’s just unfortunate that that was the last thing we said to each other. He and I were the best of friends, but as siblings who were similar in age, we had our moments.”

Alexander’s sudden death turned Lucas into an only child who struggled with survivor’s guilt. The loss affected every part of his life, he says.

“From not having a brother to talk to about things that come up with my parents, to depression and anxiety issues that I’ve suffered from over the years,” he says.

“There was a lot of pressure — the hopes and dreams my parents had for their two sons sort of fell onto my shoulders. I don’t mean to make it sound overly dramatic, but I miss him and more so as our parents got older.”

Her son’s diary offered a glimpse into his final months

In the days after the bombing, Suse Lowenstein agonized over her son’s final moments. She says she fixated on questions she knew would likely never be answered.

She wondered: Did he realize what was happening? Considering his seat number – 20D – was he among the first people to fall from the sky when the plane broke apart? She worried that wild animals in the sprawling debris field would find his remains before the investigators.

“For days we wondered … what would remain of our beautiful son? Thankfully, and I know that is a strange word to use, it meant something to us that he was found in one piece,” she later wrote as part of a memorial tribute for Syracuse University.

An autopsy report concluded that Alexander likely died instantly. His body was found days later in a four-feet deep crater on a Lockerbie farm and brought home, she says. He’s buried in East Hampton, New York, a short drive from the family home.

Scottish authorities and a team of volunteers in Lockerbie painstakingly cleaned the ash and other debris from the victims’ belongings and returned them to their families. Alexander’s box of items gave his family a glimpse into his final days.

In addition to the red jacket, the Lowensteins received several other items salvaged from the scene, including Alexander’s British rail pass, about five pages of his diary and photographs of the beaming student at Stonehenge and other tourist sites.

For his parents, the diary was a precious window into Alexander’s innermost thoughts and feelings. He wrote about a “beautiful blonde California woman” who’d caught his eye. There was also an entry about his “crazy mother” randomly whisking him off to Germany weeks before, Suse Lowenstein tells CNN, her eyes filling with tears.

The family donated the items to Syracuse University as part of an archive dedicated to victims of the tragedy, because they believed the school would preserve their son’s memory long after they are gone.

The FBI and Scottish officials are still pursuing leads decades later

Much of the airplane’s fiery wreckage rained down on a quiet Lockerbie neighborhood around dinnertime, crashing into homes with deadly force.

Of the 270 fatalities, 11 were killed on the ground. The crash scattered debris over 845 square miles, creating a massive crime scene that required thousands of American and Scottish investigators. Some of the evidence was collected as far as 80 miles from Lockerbie, the FBI says.

“It was like a battlefield. Nothing could have prepared you,” Scottish detective Harry Bell said on the 30th anniversary of the bombing.

For years, international law enforcement officials traversed the globe tracking down suspects in 16 countries.

Forensic experts recovered a scrap of clothing with bomb damage in the debris. In the piece of fabric was a tiny fragment of a circuit board, the FBI says.

The scrap of clothing was linked to a suitcase and traced to a shop in Malta, giving investigators a crucial break that led to the arrest of two Libyan intelligence operatives, the FBI says.

Investigators later determined that the bomb was hidden in a cassette recorder and packed in a suitcase that was loaded on a plane from Malta to Frankfurt, Germany, with no accompanying passenger. It was later transferred onto a flight to London’s Heathrow airport, where it was ultimately loaded onto the ill-fated flight to New York.

In 1991, Britain and the US charged two Libyan men in the bombing, which investigators believed was in retaliation for US actions against the nation’s then-dictator, Moammar Gadhafi. One was convicted of 270 counts of murder in 2001 and sentenced to life in prison, while the second one was acquitted. The convicted bomber died in 2012.

Years later, the case remains open and active. Some experts and victims’ relatives remain skeptical that the suspects arrested were the true perpetrators.

In the past five years, authorities have arrested two more suspects, one of whom has pleaded not guilty and is set to go on trial in May. The FBI says it continues to pursue leads indicating that more people may have been involved in the attack.

“The FBI and our partners … have never forgotten the Americans harmed and we will never rest until those responsible are brought to justice,” FBI Director Christopher Wray said in a statement in December 2022.

Decades later, she froze a dark moment in time

Lucas Lowenstein’s youngest son is named after his late brother. The family meets every February 25 to celebrate Alexander’s birthday. Their patriarch, Peter Lowenstein, died five years ago.

Alexander would have turned 58 next week, and the family will gather for a meal like they have in the past. Suse Lowenstein says they choose “something joyful” to embody his free spirit. Alexander loved the ocean and spent most of his free time surfing and scuba diving. His tombstone in East Hampton reads: “You were always the sunshine.”

Meanwhile, Suse Lowenstein lives with the Pan Am Flight 103 tragedy every day. Her Dark Elegy installation sits in her yard in Montauk, where people can visit between 10 a.m. and noon daily. She left New Jersey a decade after the terror attack, but her son Lucas still lives in the northern Jersey borough of Mountain Lakes.

In the years after the bombing she invited 75 women who lost loved ones in the Lockerbie bombing to her studio, where they stepped on a platform, disrobed and relived their anguish from December 21, 1988.

She asked each woman to recreate the position they assumed when they got the devastating news. Some screamed, begged and prayed. Others curled into a ball, raised their fists or covered their face with their hands. Some wept quietly.

Lowenstein says she asked the women to undress because grief strips people of everything.

“It was a very delicate process because they had to relive that exact moment when they learned their loved one had died,” she says. “The screams, the banging on the floor, the pulling of the hair … And I would quietly go around the figure and photograph it from all sides so that I could portray it truthfully.”

She worked on the sculptural work for 15 years because it gave her an outlet for her grief, she says.

The figures are arranged together in a circular pattern about 65 feet in diameter. Each figure is inscribed with the name of the woman and the person they lost in the bombing.

Inside each figure – in the chest, near the heart – Lowenstein placed a plastic bag containing a memento of the person who died: including a shoelace, a sock, an earring and photos. She says she hopes the items will be found years from now and remind people of the tragedy.

Lowenstein is part of the sculpture, too. Her figure shows her on her knees, doubled over at the waist in anguish. She placed a photo of her with Alexander in its heart.

“It’s a reminder of the tragic loss and brings mixed emotions of grief and sorrow,” she says of the large-scale artwork. “But it’s also a source of connection and comfort because it represents a gift to the victims.”

She can see the sculptures from nearly every room in her house. And on days when she especially misses Alexander, she walks through her garden while wearing his red jacket.