CNN

—

Photographer Derek Ridgers’ introduction to the Cannes Film Festival arrived in 1984, when he was commissioned to shoot the DJ and rapper Afrika Bambaataa — in town to promote his cameo in Stan Lathan’s “Beat Street” — for the music magazine, NME. “I don’t think I’d ever really thought about Cannes, or the film festival, before I went,” Ridgers, widely celebrated for his distinctive portraits of British subcultures, told CNN via email. “Every year one sees items about it on TV, but it hadn’t impacted my life in any significant way.”

Ridgers would return to the French resort town a further 11 times, during which he said he “only ever saw two films” — “Beat Street” and Thaddeus O’Sullivan’s “December Bride” (he’d been at art school with the director). “If you’re on the French Riviera and the sun’s out, why would you choose to go to the cinema if you didn’t have to?” he reasoned. Instead, Ridgers focused on the compelling and sometimes controversial scenes that unfolded around him, shooting celebrities, young models and upcoming actresses, as well as fellow photographers.

Three decades on, some 80 images from Ridgers’ archive have been brought together in a new book, “Cannes,” published by IDEA. The festival it presents is in many ways a different kind of spectacle to its contemporary iteration. This year’s edition, which runs through May 24, will largely be experienced via social media (the official Festival de Cannes Instagram page has 1.3 million followers alone, while thousands of tagged videos populate TikTok). In Ridgers’ pictures, made in the 1980s and 1990s, there’s not a single cell phone and barely a point and shoot camera; star-making-moments, political statements and fashion history were all typically reported by TV and printed media.

“My interest has always been people and, I suppose, a study of the human condition,” said Ridgers, who, alongside his professional assignments, spent much of the 1980s and the decade prior documenting London’s punks, skinheads and New Romantics. “The film festival was my first extended foray into reportage, but it’s still all people doing what people do,” he noted, reflecting on how his book “Cannes” was shaped by this same curiosity, in tandem with his rejection of the more traditional red carpet set-up.

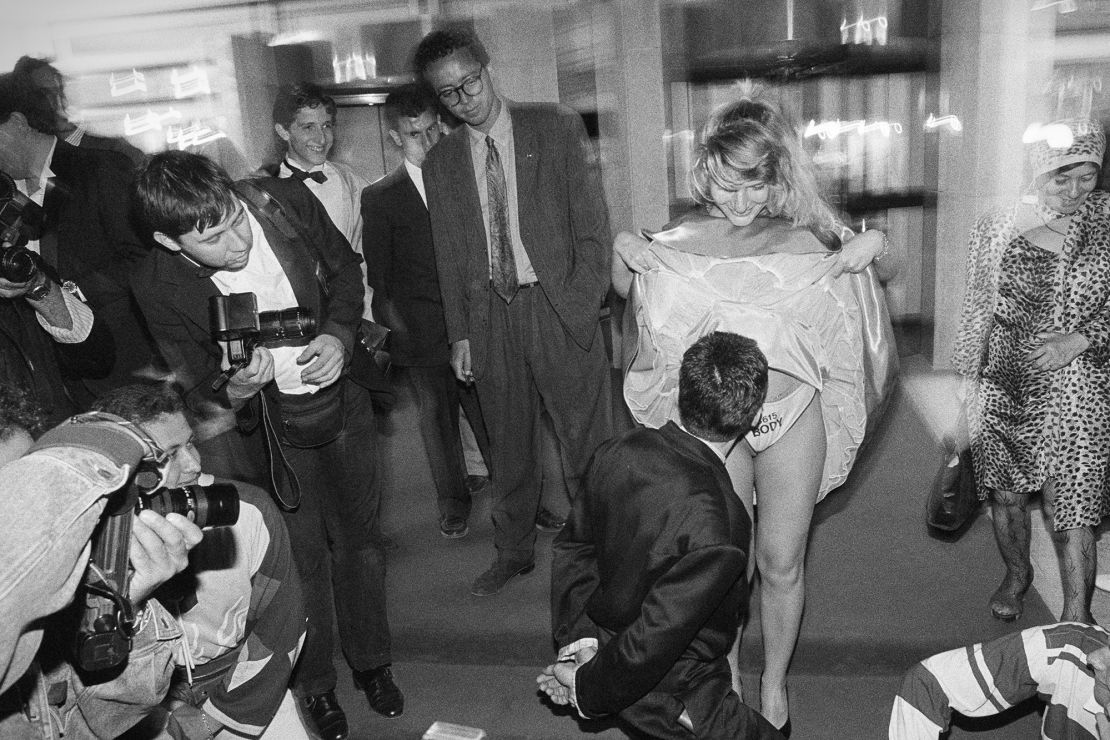

“There’s so much of life’s rich pageant on show during Cannes, there are great photographic opportunities almost everywhere,” he continued. Shooting both in color and black and white, Ridgers captured icons such as Clint Eastwood, Helmut Newton and John Waters, as well as then-up and coming models like Frankie Rayder, who appears on the book’s cover dressed in diamonds and fur (the surrounding crowd adopting casual jeans and T-shirts), and performers attending the Hot D’Or adult film industry awards too, including the late Lolo Ferrari.

“During the years I was going, the film festival seemed to become a bigger and bigger deal,” shared Ridgers. “When the porn stars were having their awards show there as well (the Hot D’Or’s ran from 1992-2001), that added a layer of craziness and made for some interesting photographic juxtapositions. The main film festival seemed to take itself awfully serious, and having the porn stars there lightened the mood somewhat.”

Young women then, adult entertainers and wannabe film stars alike, are a constant throughout the new book, posing with friends or performing for the camera; showing off in an attempt to emulate Brigitte Bardot’s culture-shifting debut at the festival in 1953, while promoting “Manina, the Girl in the Bikini.” Ridgers, adopting the gaze of a bystander, recorded it all, from the playful to the outrageous, and sometimes the outright questionable, as in the picture of another photographer taking an upskirting shot. “It seemed shocking then, too, which was why I took the photograph,” he explained. “I was appalled by the unabashed brazenness of it. Someone doing that nowadays would, rightly, get arrested.”

Stressing that he never considered himself above his peers, Ridgers further recalled that he also never felt any sense of kinship with them, and the book concludes with an image of some photographers holding and discussing one of his images, oblivious to his presence. “The whole time I went to the festival, I don’t think I had one conversation with any of the other photographers,” he said. “They shouted at me occasionally, for getting in their way, but that’s hardly a conversation. It sounds terrible, I know, but I just ignored them. I’m competitive and very focused — if I’m standing around chatting, I may be missing a good photograph.”

In “Cannes” however, the mood is one of debauchery with a light-hearted sensibility. “I’m serious about my work but this is not a particularly serious photobook,” said Ridgers, acknowledging the nature of its contents. “Most of the photographs are frivolous, and some are simply outrageous. These days, because of the French law of droit à l’image (a right to one’s image) it’s harder to publish photographs of people in public without their permission — how that works in the era of the camera phone, I have no idea. My photographs are testament to what fun, crazy and at times, ludicrous, things happened back then.”