CNN

—

Winning the trust of convicted burglar Jerry Christy was the kind of challenge undercover FBI investigator Ronnie Walker had spent years preparing for.

A founding member of the bureau’s specialist Art Crime Team, the Oregon-based agent was well-versed in art history — and trained to pose as a would-be buyer, authenticator or dealer of stolen works. Christy, meanwhile, was being covertly investigated in 2007 over the theft of several artworks, including a 17th-century etching by Dutch master Rembrandt van Rijn.

“That etching that was my entrée into his ring,” recalled Walker, who recently retired from the FBI after almost 29 years, allowing him to speak more openly about his career exposing fraudsters, forgers and traffickers in elaborate sting operations.

“At the time, I was really hyper-focused on learning about fine art prints,” added the former agent, who met Christy through a confidential source in 2007. “And I made him believe I was the kind of person who could sell a Rembrandt.”

But things got trickier for Walker, he said, when Christy’s expert accomplice got in touch.

“(Christy) took art off walls, but he wouldn’t necessarily know if it was valuable or not. He would figure that out later on,” Walker told CNN over Zoom. “So, starting off that operation, I was the expert — I knew more than him. But, pretty quickly, the tables turned… the stakes got pretty intense once I found myself going head-to-head with an art dealer.”

Around 18 months earlier, Walker said, Christy had unexpectedly vanished from the FBI’s radar. It transpired he was serving time, for an unrelated theft, at Washington State Corrections Center, court records show. By happenstance, Christy had shared a cell with Kurt Lidtke, a disgraced art dealer whom the FBI said was imprisoned for selling his clients’ works without paying them proceeds. Using the latter’s knowledge of the Seattle art market — namely the whereabouts of some of its most valuable paintings — the two cellmates began plotting an ambitious crime spree, Walker said.

“They were going to hit dozens of collections in the Pacific Northwest to the tune of several hundred million dollars,” he added.

Walker, still masquerading as an art dealer, resumed contact with Christy upon his release from prison. Christy soon carried out a successful burglary, while Lidtke was still in prison, according to court documents. And it wasn’t long before his new co-conspirator called Walker to sell him some paintings — and to sound him out, the former investigator said.

“Fortunately, (Lidtke) thought I was a dealer who specialized primarily in California Impressionists, and he was a dealer who specialized in the Northwest School (a 20th-century art movement),” said Walker, adding that they later “spent a lot of time talking about our respective areas of expertise.”

Walker used his art market knowledge to build rapport with the dealer, he said, and gained the duo’s trust by pretending to sell three of their stolen artworks. He also began gathering information about their next potential victim as the FBI prepared a trap at the target’s home.

Even as authorities appeared to be closing in — Christy was confronted by police while surveilling the property from a parked pickup truck, though he was allowed to leave the scene — Walker believes his performance had been so convincing that Lidtke was oblivious to his involvement until the very end, attributing Christy’s brief encounter with police on bad luck.

“Kurt (Lidtke) didn’t trust his instincts and blame me,” he recalled. “We’d had a long enough, and a solid enough, relationship up to that point that he didn’t listen to that inner voice saying, ‘Well, if only three people in the world knew (about the planned robbery) it must have been (him)’.”

The FBI averted the burglary and later arrested the pair, according to court documents. Walker said that incriminating recordings he collected during the sting operation helped secure convictions for both Lidtke and Christy, on charges of conspiracy and transportation of stolen goods. In 2011, they were sentenced to four and five-and-a quarter years in prison, respectively.

‘It’s easier to lie when you’re telling the truth’

The Art Crime Team, and Walker’s involvement with it, dates to the early years of the Iraq War.

As US troops advanced on Baghdad following the 2003 invasion, looters had plundered an estimated 15,000 artifacts from the country’s National Museum in just 36 hours. At the time, Walker, who had been an FBI agent since 1996, expressed willingness to investigate the thefts. Despite studying business administration and accounting at college, he gravitated toward art history courses and was interested in cases involving cultural heritage.

“I called (FBI) headquarters and said, ‘Hey, if you send a team to Iraq, put me in coach,” he recalled.

Ultimately, the FBI did not send him, or any agents, to Baghdad in 2003. But amid widespread criticism of America’s failure to protect Iraq’s cultural property — and realizing a need for experts to track down the items, or to be deployed overseas in future looting incidents — the bureau established a specialist art team the following year.

Thanks to his earlier interest and internal reputation for sophisticated undercover operations, Walker was recruited to the unit. He was one of fewer than 10 founding agents who would be trained in the history, vocabulary and, most importantly, business of art. “Within the first year of being on the team, I started taking more advanced level college courses that helped inform my approach to these operations,” Walker recalled.

The team was focused not only on thefts, from homes, galleries or archeological sites, but also forgery and trafficking rings. Given how many stolen artworks end up on the US market, it also investigated art crimes committed overseas. Today, the unit has more than doubled in size and employs experts in fields including archaeology and anthropology, as well as former art market professionals.

Since its founding in 2004, the Art Crime Team has recovered more than 20,000 items of cultural property, including thousands of items from the National Museum of Iraq (though the FBI estimates that between 7,000 and 10,000 of those remain unaccounted for). This two-decade haul is valued at over $1 billion, which Walker called “an oversized return on investment” for the FBI. And that figure doesn’t include the potential value of seized fakes that could have generated billions of dollars if successfully sold. One of the former agent’s last cases involved a dealer with “about $2 billion in inventory — that was all fake,” he said.

Recent successes speak to the unit’s broad remit. Last year alone, its investigations led to the return of a Revolutionary War-era musket to a Philadelphia museum; the recovery of a pocket watch once owned by Theodore Roosevelt that had been missing since the 1980s; and the repatriation, to Japan, of 22 artifacts looted following the Battle of Okinawa in 1945. One of the team’s most high-profile cases involved a pair of ruby slippers, worn by Judy Garland as Dorothy in “The Wizard of Oz,” that were recovered 13 years after being stolen from a museum in Minnesota.

For the latter operation, Walker posed as a Hollywood memorabilia authenticator to help lure in a suspect seeking the $1 million reward for the objects’ return, he said. To prepare, he spent time with experts at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History (which owns another pair of Garland’s set-worn ruby slippers), to study exactly how they would examine the objects.

But while there are undercover agents who can be “anything, at any time, in any place,” Walker said, he is not of that mold, despite sometimes running up to five covert operations at a time. For him, it’s all about a level of preparation — sometimes over-preparation — akin to method acting.

“It was understanding what that role should look like, and doing my best to understand that persona,” he said. “But at the end of the day, when you’re in role, the best thing to do is just be yourself. It’s easier to lie when you’re telling the truth.”

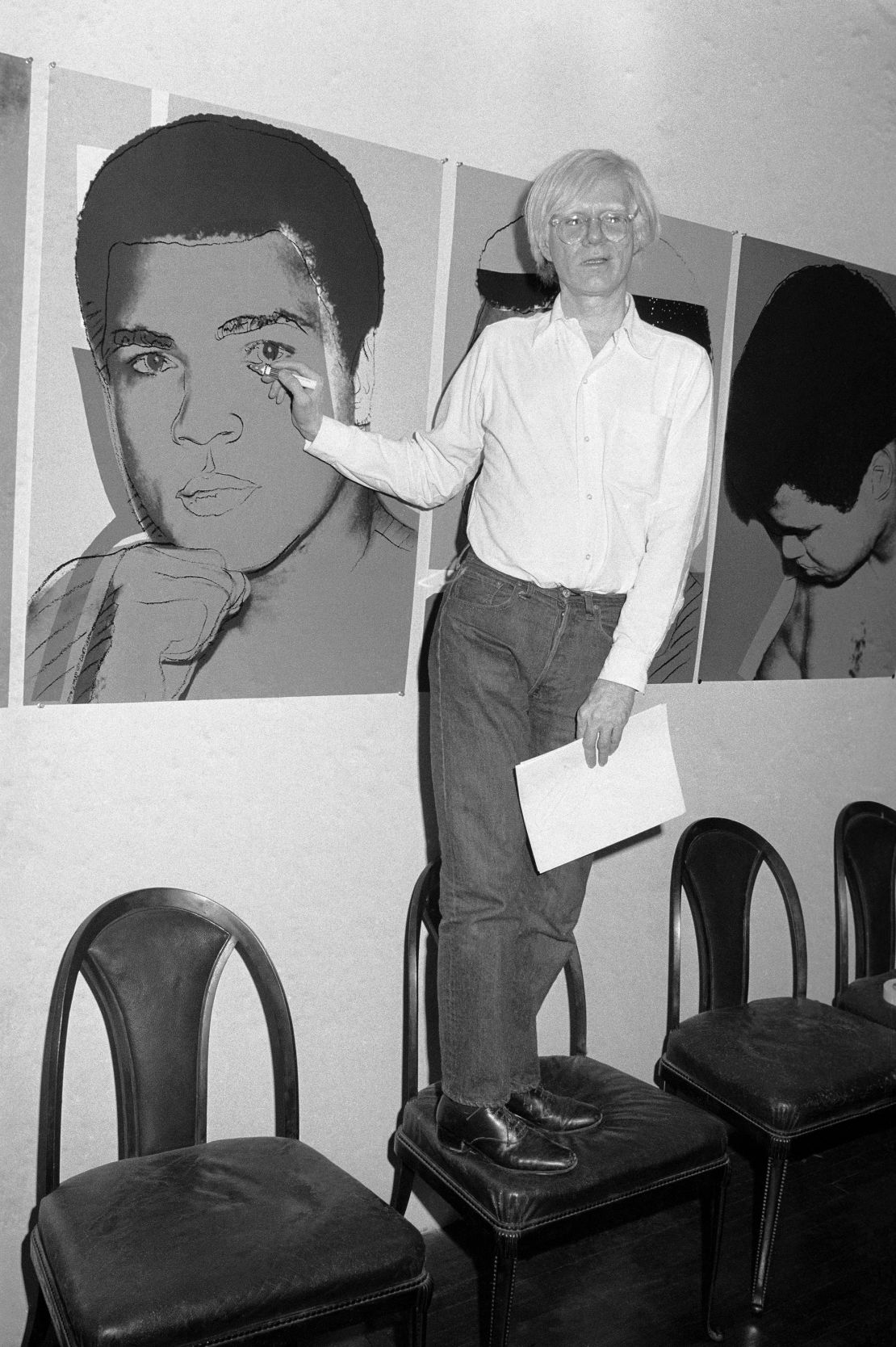

In other words: The more he knew, the more convincing he could be. “I had a lot of cases that involved Warhol, whether thefts or fakes,” Walker offered as an example. “Studying Warhol, and getting a deeper knowledge of his materials, his processes and his compositions helped me in a lot of the undercover operations.”

Walker’s performances also relied on “verbal or visual” cues typical of the professionals he was impersonating. He would sometimes dress the part, too, by wearing the expensive clothes of a high-end dealer or dressing down as the kind of uber-wealthy collector who “has so much money he doesn’t need to care about appearances,” the former agent said.

He would wear a pair of lucky Bob Ross socks, too. It was, after all, dangerous work.

“There were a few moments where I thought to myself, ‘Oh, this is how it ends,’” he recounted in a subsequent email exchange with CNN, adding: “Every single undercover meeting has the potential to escalate, even when dealing with individuals that don’t have a history of violence. In fact, I think those individuals that have no prior convictions can be more dangerous. They tend to have the most to lose.”

Heists, tip-offs and master forgers

Cases come to the Art Crime Team in various ways. Local police may alert the FBI to thefts if the stolen goods cross (or are thought to have crossed) state lines. The bureau also invites the public to provide anonymous tip-offs via its National Stolen Art File, a database containing thousands of missing paintings, sculptures and artifacts with cultural value, from candelabras to ceramics.

Usually, however, missing art only comes to the authorities’ attention when it enters, or re-enters, the market.

“Stealing the artwork is usually the easy part,” Walker said. “It’s selling the artwork that’s the hard part (because) there aren’t too many people in the world — and certainly no reputable art dealers — who want to buy stolen art. Often, the thieves haven’t really thought through how they’re going to sell the artworks.”

The FBI’s running list of “top 10 art crimes” features various high-profile items that would now be near-impossible to move on the open market. There’s the $3 million Stradivarius violin stolen from a New York City apartment in 1995, and the Pierre-Auguste Renoir painting taken in an armed robbery from a Houston home in 2011. Then there is, in Walker’s view, the holy grail of art crime: The 13 works, including paintings by Rembrandt, Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas, snatched from Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in a notorious 1990 heist.

“If you said you had a lead on them tomorrow, in any part of the world, the team would throw every resource they could at (it),” he said of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum artworks. You might also, he added, end up $10 million richer thanks to the reward offered up by the museum’s board.

Art criminals’ motivations are almost always financial, Walker said. Their downfall often shares a common theme, too, whether it’s trusting an undercover agent or seeking big-money rewards for stolen goods: greed. And while the former agent didn’t see a significant increase in art-related crimes over his two decades investigating them (if there appear to be more media reports, it’s because “we just got better at doing our job”), he believes perpetrators’ scope and abilities grew in that time.

“Twenty years ago, largely, fraud was more of the household names and the dead guys. It was the Rothkos or the Picassos. But now it’s living contemporary artists that are being faked in their lifetime,” he said, adding that technology now allows forgers to operate without conventional artistic skills. “There are printing technologies that can mimic brushstrokes. So, with a small investment and a really good high-resolution camera, you can create fakes today that rival the quality of a (master forger).”

The threat posed to living artists is now Walker’s main preoccupation. After retiring from the FBI in December, he founded the Art Legacy Institute (ALI), a non-profit helping artists protect their work and livelihoods from fraud. Having spent a career solving crimes, he now hopes to prevent them from happening in the first place.

Forgeries come in two guises: either a known work is replicated, or a new composition is created in the artist’s style and positioned as a previously undocumented work. According to Walker, the solution — to the latter, at least — is surprisingly simple: cataloging. ALI is creating a detailed digital archive, stored on its server, that he hopes would become the definitive record of an artist’s output.

“Documenting what you create, as an artist, is the most important thing you can do… There’s been no shortage of artists who grind away for (decades) to finally get recognized for their contribution, for demand to increase, and then all of a sudden, the fraudsters come out,” he said. “They start attacking the style the artists were doing 20 or 30 years earlier that is not well documented — and it’s those gaps (in provenance) that allow the fraudsters to thrive.”

As for identifying like-for-like replicas? That’s where technology now comes in. Last month, Walker’s organization announced a partnership with optical AI firm Alitheon that can create a unique “digital fingerprint” for any artwork — thousands of data points recording miniscule surface details, invisible to even the greatest forger’s eye.

“It is simple to use and scalable, and it just works,” Walker said, joking: “Even an old, retired FBI agent can use this tech.”