CNN

—

Ernest Cole was dying. Lying in a hospital bed in Manhattan, New York, thousands of miles from his homeland of South Africa, the photographer and documenter of apartheid was faced with a bitter irony: he was leaving the world just as his nation was being reborn. The date was February 11, 1990, and on TV, Cole watched Nelson Mandela emerge from prison, taking the final steps of his long walk to freedom. A week later Cole succumbed to pancreatic cancer. He was 49.

A brief obituary in the New York Times mentions Cole’s seminal work, “House of Bondage,” a shocking exposé of apartheid in the 1950s and ’60s. Published in 1967 and immediately banned in South Africa, “For many Westerners, it was their first sight of what life was like for blacks in the South African mines, compounds and townships,” the obituary notes.

“He left South Africa and resettled in the United States in 1966,” it ends, before listing his survivors. The statement offers no hint of the circumstances behind his expatriation and the years that followed. He “resettled” — a word that reads like a conclusion to Cole’s story.

Cole never published another book of photography, but nor did he put down his camera when he arrived in New York City. For decades, these photographs were thought lost. Now this body of work is finally emerging; tens of thousands of photographs and reams of writing, forming a second chapter for Cole, the artist in exile.

This story has been given life by filmmaker Raoul Peck and actor LaKeith Stanfield, both Oscar nominees, in the documentary “Ernest Cole: Lost and Found.” The film, which premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in May and debuted in US cinemas in November, comes after “Ernest Cole: The True America,” a book collecting more than 260 photographs from the same new trove, published by Aperture in January with a preface from Peck.

The Haitian filmmaker, whose work spans fiction and non-fiction, has crafted cinematic reappraisals of Black historical figures, including American writer James Baldwin (“I Am Not Your Negro” [2016]) and Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of present-day Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). His filmography prompted Cole’s estate to contact the director after it took possession of thousands of previously unseen photographic negatives in 2017.

Peck initially turned down a film, he told CNN in a video interview, but two years later, had a change of heart.

He quickly realized Cole’s voice needed to be front and center. “Too many people have written about him without asking what his own opinion (was) and what his goals and ambitions were,” he said. “I thought, ‘let the man talk.’”

The director penned a screenplay based on Cole’s diaries and letters written in exile, as well as the new photos, and hired Stanfield to voice Cole.

Not looking for an impression but authenticity, he cast the American actor over a South African. “His voice is not pure, it’s not academic,” he said. “I knew that’s what I needed.” The two bonded over their mutual love of photography, and there were tears in the recording booth when Stanfield reached the last, saddest passages of the photographer’s life.

Life in exile

Born near Pretoria in 1940, Cole received his first camera as a teenager. He grew up to become a freelance photographer for DRUM, a South African magazine covering Black culture, and later chief photographer at weekly newspaper Bantu World, riling officials with his frank images. He was arrested in 1966 and given the choice to turn informer or go to prison. Instead, he fled to the US with his negatives.

“House of Bondage” published the following year. “That was the first time you basically have a camera inside the belly of the beast,” said Peck.

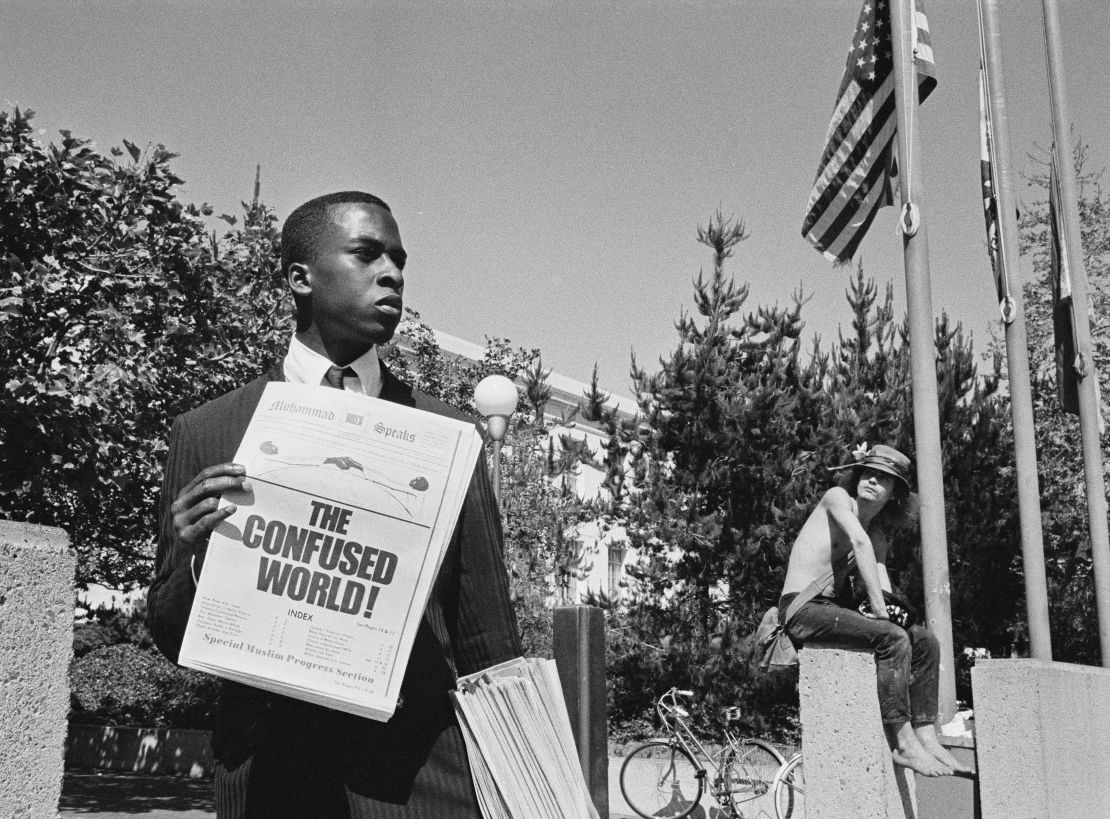

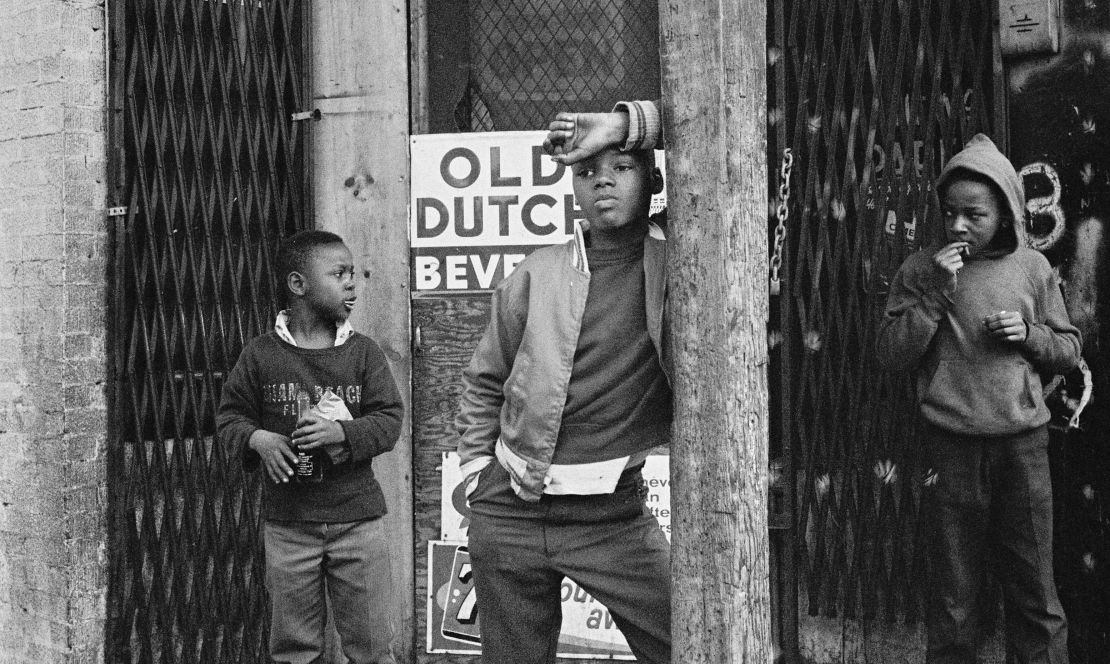

Cole struggled personally and professionally in the United States. He was stripped of citizenship by South Africa, making travel difficult, and limited by his US patron the Ford Foundation to documenting Black life, mostly in New York and the Jim Crow South. “They put (him) in a box,” said Peck.

The filmmaker shows us a selection of these images. Some are joyous and carefree — particularly those in Harlem; others convey hardships incubated by institutional racism spanning urban and rural Black America. There are direct parallels with his South African oeuvre, yet Cole’s peers judged this work lesser than his apartheid photography.

“Who (were they) to say he lacked passion? (That) it doesn’t show the same risk-taking?” Peck bristled.

“Liberal white gatekeepers, sometimes they are the worst, because they have this additional paternalism,” he added. “They are sure they do (things) for your own good. It’s not even ideology, it’s about, ‘We know it’s difficult, but we know best for you.’”

Has the filmmaker experienced this too? “All the time, even today,” he said. “Except that today I don’t care, and I know how to respond.”

There are plenty of parallels between Peck and his subject. Born in 1953, he and his family left Haiti (“my father” – prominent agronomist Hébert B. Peck – “was arrested twice”) and lived between the DRC, the US and France, before Peck moved to Berlin to study aged 17. (The director would later return to Haiti a notable filmmaker, and served as minister of culture between 1996-97.)

“(In Berlin) most of my friends, who were my elders, were exiled people, the former head of a student movement in Brazil or Nicaragua, a representative of the ANC (African National Congress) in Berlin, a representative of the SWAPO (the Namibian independence movement),” said Peck.

In the film, Cole despairs, “exile is destroying us one by one.”

“You leave your country heartbroken,” the director said. “Then once you are elsewhere, there is not a single day that you don’t think about where you came from — not one single day — to the point you become crazy, paranoiac, withdrawn. I’ve seen all those examples, whether in my own family or with neighbors or people from the Haitian community.”

“It didn’t take long for me to understand every word (Cole) was saying,” he added.

Work dried up for Cole by the early 1970s. The Ford Foundation project went uncompleted. He experienced poverty and homeless on the same New York City streets he had photographed, and according to Peck’s film, didn’t pick up a camera for years.

Peck attributes some of this decline to Cole never being able to escape his apartheid photography — or being allowed to.

Cole laments he did not want to be “a chronicler of misery.” “It was never going to work,” he says of photographing the segregated South, “a territory ironically similar to mine (South Africa).”

Yet Cole was not permitted by patrons to expand into other areas of photography like his White peers, Peck argues: “I think that’s what destroyed him.”

An unexpected find

After his death, Cole’s time in America became a footnote with scant evidence attached.

Then in 2017, Cole’s nephew, Leslie Matlaisane, chairperson of the Ernest Cole Family Trust, was contacted by Swedish bank SEB out of the blue, asking if he would collect three safety deposit boxes. Inside were around 60,000 Cole negatives, spanning South Africa and the US, plus his notes and contact sheets. Mysteriously, there were no records associated with the boxes and few opportunities for Matlaisane to ask questions.

How Cole’s archive ended up in the bank vault, why they were released and why now has been the subject of fierce speculation.

Peck features footage of the handover in his film, and says he has a theory of what happened, but he “didn’t want to burden” the documentary by focusing on this outstanding mystery.

The film is heavy enough as is. Hearing Stanfield narrate what Cole called his “slow disintegration and descent into hell” in the US is desperately sad. So too is his conclusion that “New York is a soulless city.” The thrum of the city’s streets and the vitality of its people, as captured by his lens, tells a different story.

The reappraisal of his American photography — “sorely needed,” “cementing the legacy he deserves” — comes too late for Cole.

“He left South Africa and resettled in the United States,” according to the New York Times. The truth Peck brings to us is that Cole was anything but.

“Ernest Cole: Lost and Found” debuted in New York cinemas on November 22.