CNN

—

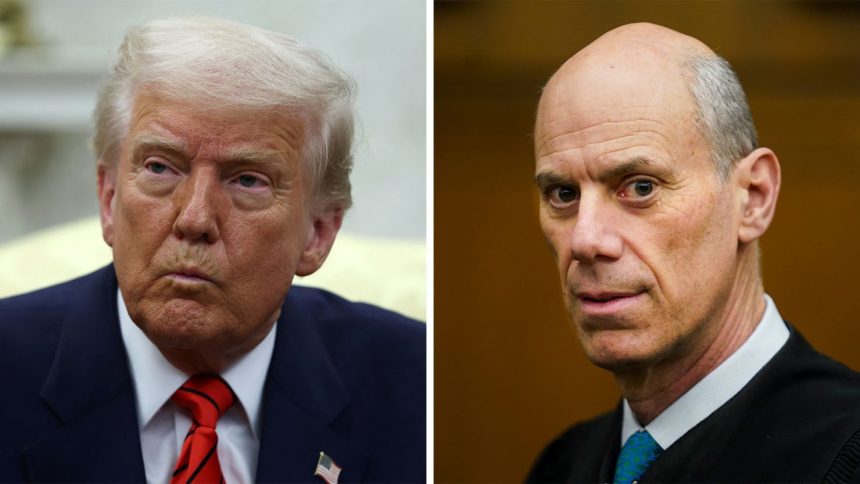

Judge James Boasberg – who ruled Wednesday that the Trump administration showed “willful disregard” for his mid-March order halting deportation flights amid dispute over the legality of the removals – is the first judge to find “probable cause exists” to hold administration officials in criminal contempt.

But the legal fight over whether federal officials defied Boasberg’s orders is playing out on a larger tapestry of administration scorn and recalcitrance towards the judges that have curtailed President Donald Trump’s agenda, with the tone set at the top by Trump himself.

Trump officials have launched personal attacks against Boasberg and other judges on social media and in public appearances. Government lawyers have claimed ignorance when asked basic questions about the facts underlying legal disputes. And faced with rulings pausing Trump policies, the administration has expressed a remarkable disdain for judicial authority in the guidance its offered agencies for following those judges’ commands.

“It’s breathtaking in its audacity and lack of decorum,” said retired Judge John Jones III, a George W. Bush appointee who served on a federal court in Pennsylvania. “It’s unlike anything I have ever seen from the Justice Department and, really, in fact, any lawyers who practice in federal court.”

The administration’s cavalier attitude has been front and center in the case concerning the mistaken deportation of a migrant in Maryland to a super-prison in El Salvador. Those proceedings reached a new level of intensity after the Supreme Court last week left mostly intact an order from the district judge requiring the Trump administration to “facilitate” the migrant’s return to the United States.

At a Tuesday hearing before US District Judge Paula Xinis, DOJ attorney Drew Ensign tried to challenge how she was interpreting the Supreme Court’s instructions and indicated that the administration would appeal any order she issued broadly defining the term “facilitate,” the key verb the Supreme Court embraced in its order last week.

“The Supreme Court has spoken. I’m cleaving as closely as one can cleave to the Supreme Court. My order is clear. It’s direct. There is, in my view, nothing to appeal,” Xinis pushed back. The department has since appealed her April 11 order, issued the day after the Supreme Court weighed in, directing the administration to take steps to facilitate the migrant’s return and to provide her information about what those steps were.

In that case, as well as in their public messaging around the various legal disputes, top Trump officials have embraced the idea that, no matter what lower courts say, they have the Supreme Court on their side.

White House deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller, for instance, falsely described the Supreme Court as ruling 9-0 in its favor on the question of whether a court could order the government to take steps to try to bring Abrego Garcia back. What the unsigned majority opinion said was more ambiguous, and three liberal justices wrote separately to make clear they agreed with the judge’s directive that government take steps to bring the migrant, Kilmar Abrego Garcia, back.

“What the administration is trying to do is to detach the Supreme Court from the rest of the judiciary and say, ‘We’ll listen to the Supreme Court, but we don’t have to trifle with the lower courts,’” Jones said.

Swipes at judicial power

During the first Trump presidency, judges were no strangers to being the subjects of his infamous social media diatribes, prompting security concerns about the judges’ safety.

The top officials in his second administration are frequently singling out the judges with jeers as well.

White House deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller called Xinis a “Marxist” who “now thinks she’s president of El Salvador.” Attorney General Pam Bondi alleged that Boasberg was “trying to protect terrorists who invaded our country over American citizens.” And Trump amplified the idea that Boasberg should be impeached.

The derisive rhetoric has seeped into the administration’s more formal statements too.

When the Justice Department was required communicate to agencies that a judge had paused a Trump executive order attacking a law firm’s ability to engage with the federal government, the Bondi-authored memo said that “an unelected district court yet again invaded the policy-making and free speech prerogatives of the executive branch.”

US Citizenship and Immigration Services reworked a notice posted to its website announcing that a Trump immigration policy had been paused by a court in California, according to court filings from the policy’s legal challengers. The initial version of the notice announced the court’s ruling and its impact on the policy using straight-forward language. But a few days later the notice was redrafted to take several swipes at the judge’s ruling.

“The Administration is committed to restoring the rule of law with respect to Temporary Protected Status (TPS),” the redrafted notice said, referring to the immigration program that Trump was blocked from winding down. “Nonetheless, on March 31, 2025, Judge Edward Chen, a federal judge in San Francisco, ordered the department to continue TPS for Venezuelans.”

Samuel Bagenstos – who served as general counsel at two different federal agencies during the Biden administration, and who has also worked in top positions at the Justice Department – said the administration’s tone was like nothing “I can think of in my 30-plus years as a lawyer.”

“We made very strong arguments to the courts that we were appealing to that these decisions were wrong,” Bagenstos, now a University of Michigan Law professor, said of his time in the Biden administration. “But when we were instructing our clients on complying with the decisions, we tried to take seriously that the courts had the power to order us to do the things that they were ordering us to do.”

In the court proceedings themselves, the Trump Justice Department has been curt in its refusal to provide judges with facts that would help make sense of the disputes before them.

US District Judge Ellen Hollander – who is overseeing a challenge to the access the Department of Government Efficiency has been given to sensitive Social Security Administration data – requested that the agency’s acting commissioner attend a Tuesday hearing to clear up discrepancies in the internal documents and statements the government submitted in the case. Hollander previously called out acting commissioner Leland Dudek out for telling multiple media outlets that he would be forced to shut down the agency because of her emergency order limiting DOGE data access – with the judge making clear that was an incorrect interpretation of her directives.

At 10 p.m. Monday, the department informed her that Dudek would not be participating in the proceedings, pointing only the evidence the government had already put forward and “the demands on the Acting Commissioner’s time.”

Hollander repeatedly remarked during Tuesday’s hearing that not having Dudek available to answer her questions was hindering her ability to understand key details about the legal dispute.

At an earlier phase in the case concerning the wrongly deported migrant, a career DOJ attorney showed remarkable candor about the struggle he was facing to obtain from government officials the information he knew the judge would seek.

“Your Honor, I will say, for the Court’s awareness, that when this case landed on my desk, the first thing I did was ask my clients that very question,” the attorney said when Xinis asked him why the US couldn’t ask El Salvador for Abrego Garcia back. “I’ve not received, to date, an answer that I find satisfactory.”

That attorney has since been fired, with Bondi suggesting that he had failed to “zealously advocate on behalf of the United States.”

Ensign, a political appointee who has taken over arguing the case, has been much more disciplined in the non-answers he has given the judge. At a hearing last week – during which he made his arguments seated a defense the table, rather than standing at the lectern – he claimed to be unable to answer even the judge’s questions about Abrego Garcia’s current location.

Days later, the administration still has not provided direct responses to the judge’s queries about how the government was working to bring back the migrant. Instead, at a Tuesday hearing, Ensign tried to point to Oval Office remarks from Trump, the Salvadoran president and Bondi.

Xinis shut down that offering – noting that the off-handed comments from President Nayib Bukele to a reporter would not be accepted in a court of law – and she ordered two weeks of “intense” discovery, including with depositions, to get to the bottom of the administration’s inaction on her order.

“By stonewalling judges’ requests for information, they’re just making it that much harder for judges to enforce compliance,” Peter Keisler, a former top Justice Department official who served as an acting attorney general under George W. Bush, told CNN.

Eyes on the Supreme Court

When calls on the right reached a fever pitch for impeaching Boasberg and other judges that ruled against Trump, Chief Justice John Roberts issued a notable statement – without naming any judge in particular – asserting that the normal appellate process, and not impeachment, was the “appropriate response to disagreement concerning a judicial decision.”

That statement has done little to cool down temperatures. Even when it’s ruled against the administration, the Supreme Court majority has not used those opportunities to directly address how the administration has handled itself in lower courts. The high court’s majority has seemed to go out of its way to avoid provoking further conflict, Bagenstos said.

“If you’re the Trump administration, you might think it’s a good bet that you can continue to be disrespectful to these lower court judges and nothing is going to happen negatively to your legal position as a result,” Bagenstos said.

Not helping the situation, legal observers say, is that the Supreme Court has used vague, and arguably mealy-mouth language in the brief emergency orders its issued instructing lower courts to “clarify” their commands for the government.

“It seems to me that it’s getting worse, the heat is rising,” Jones, the former judge, said. Roberts and the other justices are “going to have to start protecting lower court judges.”