Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

CNN

—

Thousands of ancient butchered human bones found in a deep shaft in southwest England have pointed archaeologists to a grim chapter of British prehistory that occurred during the Early Bronze Age.

Analysis of the more than 3,000 bones has suggested that unidentified assailants violently killed at least 37 men, women and children before butchering and cannibalizing their victims between 2210 and 2010 BC at a site called Charterhouse Warren, which is located in Somerset. Then, the attackers tossed the remnants of the bodies down a 49.2-foot (15-meter) natural shaft linked to a cave system.

The grisly find represents the largest example of interpersonal violence from this period in Britain, according to the authors of a study describing the findings, which published Sunday in the journal Antiquity.

The bones are rare, direct evidence that point to a cycle of violence at a time during the Early Bronze Age that experts had once considered to be largely peaceful in Britain. Most of the hundreds of human skeletons recovered from 2500 to 1500 BC in the country typically have not contained evidence of brutality, the study authors said.

“We actually find more evidence for injuries to skeletons dating to the Neolithic period (10,000 BC to 2,200 BC) in Britain than the Early Bronze Age, so Charterhouse Warren stands out as something very unusual,” said lead study author Rick Schulting, professor of scientific and prehistoric archaeology at the University of Oxford, in a statement.

“It paints a considerably darker picture of the period than many would have expected.”

The researchers believe the intent behind the extreme treatment of the victims’ remains was intended to dehumanize them as revenge after some perceived grievous offense. But trying to determine the exact motive from unknown attackers during a time before written documents existed in the region is proving difficult.

Uncovering a horrific site

Excavations took place at the Charterhouse Warren shaft, which is part of a limestone plateau, in the 1970s and 1980s as part of an effort to better understand the subterranean cave system. There, researchers unearthed piles of buried human bones, mixed in with cattle bones, that told the story of mass violence striking an ancient community.

Multiple studies have covered the site and its contents since their discovery. But the find drew Schulting’s attention in 2016 thanks to his colleague and study coauthor Dr. Louise Loe, head of Oxford Archaeology’s Heritage Burial Services, who excavates and analyzes human skeletons from archaeological sites. Loe had studied the remains and knew Schulting was interested in documenting evidence of prehistoric violence.

“We examined some of the material together and it quickly became clear that the extent of modifications to the bones were far beyond what either of us had ever seen,” Schulting said. “So the project developed to tell the story of the site.”

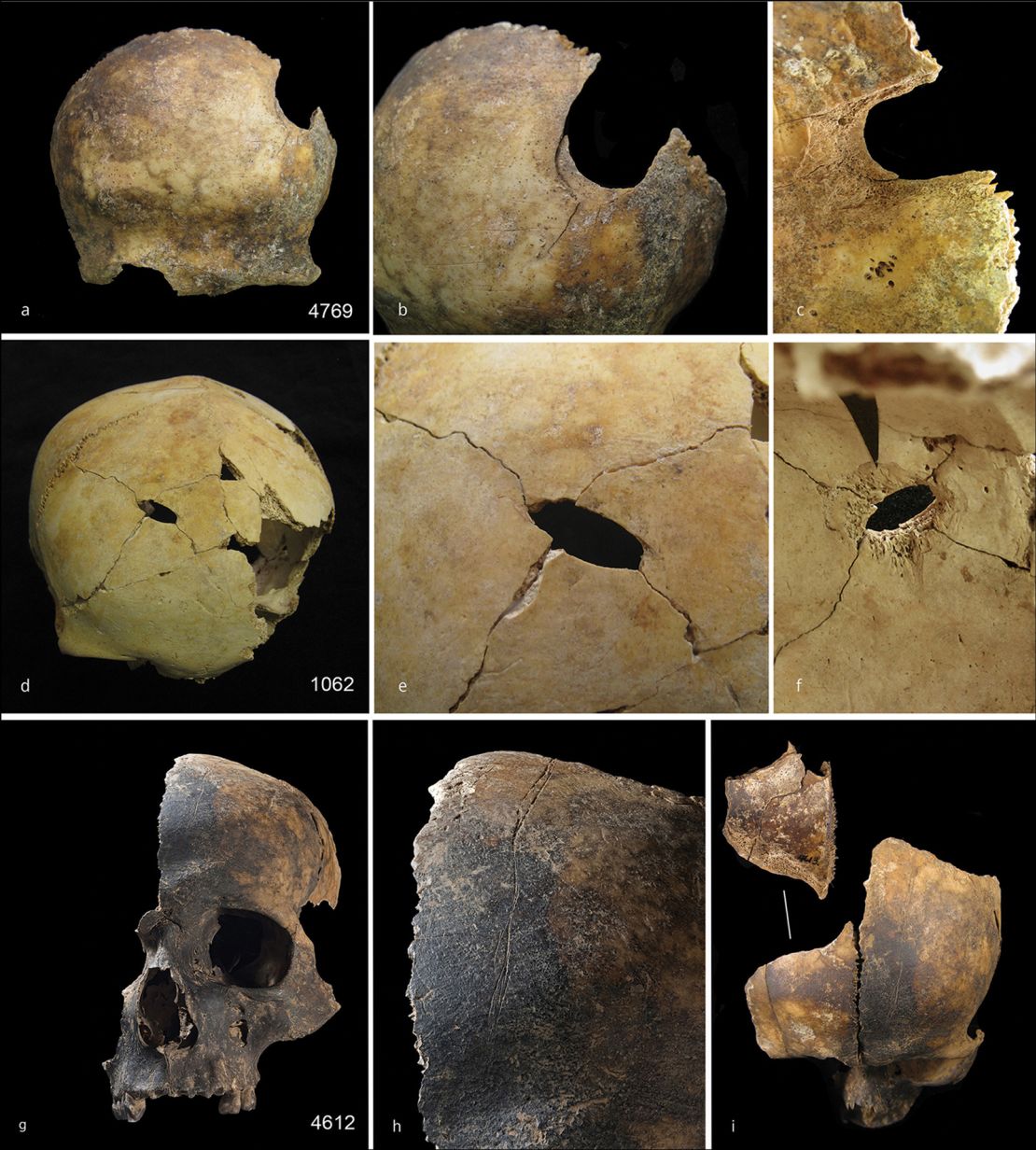

An analysis of the bones revealed that many of the skulls showed fatal impacts from blunt force trauma, but the violence didn’t end there. Numerous cutmarks covering the bones and fractures at or near the time of death showed that the victims’ heads, arms, feet and legs had been removed from their bodies using stone tools. There was also evidence to show that their scalps and skin had been removed, as well as some heads with removed lower jaws and potentially tongues.

“In addition, a small number of small bones of the hands and feet exhibit fresh bone crushing fractures that are consistent with the flat molars of omnivores, including humans, rather than the sharper punctures caused by carnivores,” the authors wrote in the study, noting that the body parts were buried quickly after being butchered and cannibalized, making scavenging by animals highly unlikely.

The bone analysis also showed that almost all of the victims were local to the area, suggesting that the attackers invaded the community to carry out their brutal acts. What’s more, the extreme manner in which the remains were handled is beyond what Schulting and his colleagues have seen from remains of ancient animals who were butchered.

“The most surprising thing is the sheer extent of the butchery of the bodies,” Schulting said. “They were killed with blows to the head, and then systematically dismembered, defleshed, bones smashed apart.”

The researchers believe the bones are all from a single event. But given that there are different layers of material found within the shaft, the animal and human remains within it may have been deposited “over decades and up to a century or so is possible,” according to the study.

“The location itself may be the common denominator; the natural shaft and large underlying cave system inviting comparisons with a portal to the underworld,” the study authors wrote.

But the biggest question is why this community was brutalized in the first place. In order to glean the reasons, the team looked back over time for similar violent events.

A history of violence

For context, the researchers looked to the nearby Paleolithic site of Gough’s Cave in Cheddar Gorge, just 1.9 miles (3 kilometers) to the west. There, prior excavations revealed six individuals whose bones had been dismembered and butchered, including potential human chew marks on hand, foot and rib bones. But there is no evidence that the people who cannibalized them actually killed their victims, implying that the cannibalism was actually a form of funerary ritual, the study authors said.

Researchers have found evidence of warfare carried out with bows and arrows at Bronze Age sites, and evidence exists from the Early Neolithic about 1,500 years before Charterhouse when weapons like swords began to appear in the historical record, Schulting said.

But the Charterhouse Warren victims showed no signs of putting up a fight, suggesting a substantial part of a community was caught off guard or held captive and massacred, and that how they were dealt with afterward was far different from ritual.

There are a few limited examples of victims of violence being buried, like a young male found in a ditch at Stonehenge who was shot multiple times with arrows, according to the study authors. But funeral rituals largely included cremation or burials of multiple individuals together, rather than what was found at Charterhouse Warren.

The researchers don’t believe the people were killed as food due to starvation, given the abundant amount of cattle bones found mixed in with the human bones.

Instead, the study authors believe cannibalism may have been an extreme form of dehumanizing the victims by “othering” the deceased, or eating their flesh and mixing their bones with cattle bones as a way to liken the victims to animals, the researchers said.

Innovations in weaponry, like daggers, suggest that interpersonal violence was occurring at the time in Early Bronze Age Britain, said Barry Molloy, an associate professor in the school of archaeology at University College Dublin. Enemies could be considered “others, people so distant from your group that extreme violence against them became acceptable,” said Molloy, who was not involved in the study.

Population turnovers in Britain within the centuries surrounding the event suggest exceptional othering was happening as new groups took over parts of Britain, Molloy said.

“How far people in prehistoric Europe were willing to dehumanise and brutalise the othered enemy group is writ large at (Charterhouse Warren),” he said.

But what could have necessitated such a dramatic act? The study authors don’t believe the attackers were fighting for control of resources at the site, and climate change didn’t seem to have an impact on conflict in Britain at the time.

While it’s impossible to know the ancestry of the attackers, there is no evidence to suggest a clash of communities with different ancestries or ethnicities.

An extreme form of revenge

Understanding motivations in prehistory before written records existed in Britain is incredibly challenging, Schulting said. But the sheer number of victims means there must have been an even larger number of aggressors, he said.

Analysis of DNA from the bones is in progress to determine how closely related the victims were, and the research team also intends to study the animal bones going forward, Schulting said.

And there is evidence within the teeth of two of the child victims that they had the plague, based on previous research, although it’s unclear how it may have been linked to the violent episode.

“Possibly this was seen as revenge for some transgression,” Schulting said. “Such violent acts can emerge in a climate of anger and fear — there is evidence that some individuals had the plague, which may have contributed to a sense of fear and uncertainty. Tensions may have built up from relatively innocuous beginnings (theft, accusations of witchcraft, and so on) and then escalated out of control.”

Molloy said that while the theory of a single massacre is compelling, it’s more chilling to think that this phenomenon took place across multiple instances, possibly normalizing cannibalism.

“Sometimes a single site can radically change our perceptions, and I think that Charterhouse has the potential to do just that,” Schulting said. “The extreme violence seen here is unlikely to have been an isolated incident. There would have been repercussions, as the relatives and friends of the victims sought revenge, and this could have led to cycles of violence in the region.”