Editor’s note: A new series “New Orleans: Soul of a City” explores the many ways the city communes with its history – through music, food, sports and tradition – revealing how, 20 years after Katrina, New Orleans is louder and more resilient than ever. The four-part series premieres Sunday, August 24, at 9 p.m. ET/PT.

On August 28, 2005, thousands of people lined up to enter the Superdome, just as they had done countless times since the stadium opened 30 years before.

Only this time, they weren’t getting ready to watch the beloved New Orleans Saints. They were seeking refuge from one of the worst natural disasters in American history: Hurricane Katrina.

Speaking to CNN for “New Orleans: Soul of a City” – a new four-part documentary which premieres Sunday, August 24 – former Saints running back Deuce McAllister remembers the scene.

“It was a last refuge for people,” he recalls. “It became, ‘If you don’t get here, you don’t have anywhere else to go.’”

A nation’s shame

“The Big Easy” was already used to having the eyes of the world fixed on the Superdome.

Around 80,000 people turned out to see Pope John Paul II address a youth rally in 1987. Two billion people around the world tuned in to watch Muhammad Ali defeat Leon Spinks in 1978. And everyone from the Rolling Stones to Michael Jordan to George H. W. Bush had appeared under the iconic stadium – now known as the Caesers Superdome.

That’s not to mention the Saints themselves, who became part of the fabric of the city and finally had their first winning season in 1987 after 20 years of disappointment.

But Katrina was different. On the morning of August 28, with the potential damage to the city becoming clear, New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin ordered people to evacuate. Those who could not, he said, should head to “shelters of last resort,” one of which was the Superdome.

“We were trying to get people in as quickly as we could because the rain was starting to fall, the winds were picking up,” former Superdome General Manager Doug Thornton tells CNN. “So we eventually just let everyone come onto the football field to get them out of the rain.”

The first night passed without many problems, but that all changed when Katrina made landfall on the morning of August 29. Before long, a section of the roof had been torn away and rain was pouring into the stadium.

“I was so afraid that someone was going to get killed from some type of piece of debris that would fall out of the stadium,” says Thornton. “I don’t think evacuees realized the danger they were in. Many of them were huddled together with blankets over the heads shielding themselves from the falling rain.”

Panic began to set in. Drinking water was limited, much of the stadium was left without power, plumbing systems began to fail and there were even reports of deaths. It was not long before the Superdome became what Thornton – who had expressed reservations at the prospect of using the stadium as a shelter without adequate staffing and supplies – calls “a symbol of misery and suffering.”

The rest of the country watched in horror as images from within the stadium looked far more akin to a warzone than a sports venue.

“The pictures from the Superdome, it’s like the worst nightmare in the world,” former New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu tells CNN. “American citizens basically stuck without any help, just because everybody and everything was basically on their back. So it was a really difficult space for people to be in for a period of time.”

For Devery Henderson, who had started playing for the Saints only a year before, the shock was perhaps even more profound.

“You’re seeing the venue that you play your games in, the crowd cheering you on,” he recalls to CNN. “Then to see it in that state, it was just mind-blowing.”

With supplies running dangerously low and conditions only continuing to worsen, the evacuation of the Superdome began on August 31, as a convoy of buses lined up to take people to the Houston Astrodome.

“We came back a week later to assess the damage. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing,” recalls Thornton. “Imagine the worst in your mind, and it was worse than that.”

As Thornton was flown away from the stadium, he looked back across New Orleans and wondered if he would ever be back.

“I wept all the way to Baton Rouge on that helicopter flight,” he says. “I just sat and reflected on what had happened to our city, and what had happened to us, and the people in the Superdome.

“I just couldn’t imagine the city would ever recover. It was just a deep sense of despair.”

And yet, despite the tragedy of the disaster and the controversy over how it had been handled, some Louisianans still hung on to sports to help get them through.

McAllister, who had the chance to come back to New Orleans as rescue efforts were taking place, was caught off guard by a question he was asked by one survivor.

“Did the New Orleans Saints win the football game?”

When the Saints came marching back

With the team temporarily relocating to San Antonio in Texas, Thornton and his team had a huge job on their hands trying to repair the Superdome. Three quarters of the roof membrane had been torn off, and conditions within the stadium were even worse.

Initial estimates were that it might take more than two years to rebuild the venue. Yet, thanks to the efforts of 35 contractors and 850 workers – many of whom worked seven days a week – the Superdome was “football ready” in time for the new season in September 2006.

“The day that we reopened the dome, it was like Mardi Gras and Jazz Fest coming together at one time,” remembers Thornton. “I looked around and I saw the faces of the people there, and the faces were happy faces. And I had this visual of people huddled, protecting themselves from the rain.

“And now I’m looking into the stadium and I’m seeing these happy faces, people standing and cheering. It was the most amazing feeling.”

For Landrieu, the first game back served to reassure Louisianans that there was a future after Katrina.

“When the Saints came back into that building, and we all saw each other for the first time in a long time, and we had the glorious Saints Day, that’s the moment when we knew we were going to survive,” he says. “It was a big moment for us, and people in New Orleans remember that very moment, and the Saints gave us that.”

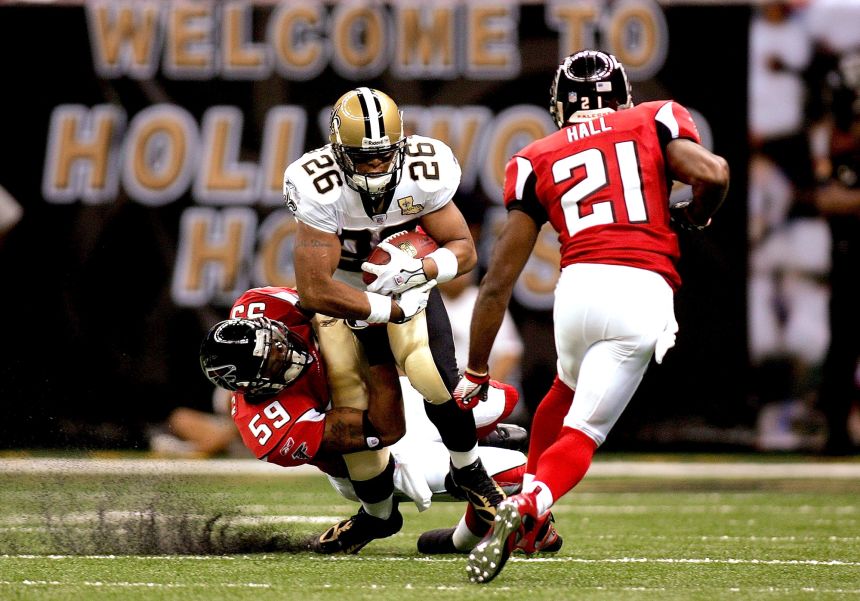

McAllister, who led the game in rushing yards that night as the Saints beat the Atlanta Falcons 23-3, was just happy to give the fans something else to focus on.

“You knew, as a player, some of the things that they were dealing with,” he says. “And the hope was, ‘You don’t have to worry about the roof. I don’t have to worry about FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency), or all the things that you’ve had to deal with over the last year. I don’t have to worry about that. And for three hours, I get to enjoy my team.’”

The Saints won 10 games that year for only the second time since 1992, and – after missing the playoffs the next two seasons – dazzled their way to a 13-3 year and their first ever Super Bowl victory in February 2010 behind head coach Sean Payton and quarterback Drew Brees.

It is impossible to say for sure whether Katrina galvanized the franchise. And, of course, no amount of sporting success will ever make people forget the tragic events of 2005.

But, for players like two-time Super Bowl champion Malcolm Jenkins, being able to win football’s biggest prize for the city of New Orleans was like an extra badge of honor.

“To be able to take this team and this city all the way to a Super Bowl and beat Peyton Manning and the Colts as underdogs was one of those things that most people waited their entire lives to see,” he tells CNN’s Brianna Keilar.

“That particular moment really brought the entire city together as proof that this is a place that is resilient, that can rebuild and be better.”

As far as Henderson is concerned, that desire to rebuild was one of the key factors in spurring the team on.

“For us to win at a time when the city wasn’t at its full strength, that’s just incredible,” he says.

“We did it with the support of those displaced people. Those people that were called refugees. We did it with those people.”