When a powerful thunderstorm spawns a tornado, people have what feels like only moments to gather their family and get to a safe place.

“Every minute counts,” said David Stensrud, a professor of meteorology at Penn State and former research meteorologist at the National Severe Storms Laboratory, a division of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Quick-forming tornadoes are still extraordinarily hard to predict. But 40 years of advancements in meteorology have extended the time between an emergency alert and tornado touchdown from just a few minutes in the 1980s to around 13 to 15 minutes today – quadrupling the lead time, according to Stensrud.

Those precious extra minutes can save lives — they allow people time to take shelter in a basement or empty bathtub to ride out the storm, and they give emergency responders crucial information about the tornado’s path so they can prepare for rescues once danger has passed.

Better forecasts are reducing deaths. Weather-related fatalities from hurricanes, floods, tornadoes and lightning strikes have decreased since 1940, as forecast accuracy improved, and Americans became more aware of the risks posed by strong storms.

But former top forecasters in the National Weather Service are anxiously watching as the Trump administration cuts meteorological staff, with more impending budget and staff cuts on the way. Some cuts have even included the “hurricane hunters” who literally fly planes into the eye of a hurricane to gather data.

“You may see more people die as a result; you will see economic loss; at NOAA our mission is to protect lives and property,” said Andy Hazelton, a member of the specialized flight team known as hurricane hunters at the National Hurricane Center. Hazelton was one of the probationary employees fired several weeks ago; he has since been put on administrative leave but is not actively working.

Some high-ranking NOAA leadership warned cuts at the already overworked agency could reverse decades of progress made on public forecasting that is free for every American.

“Any reduction in staffing at a weather forecast office will result in either delays in the forecast being issued, and watches and warnings as well, or an erosion of quality,” said Rick Spinrad, the former NOAA administrator under Biden. “It wouldn’t surprise me at all if at the end of the season we’ve gone back by a few years – maybe a decade – in terms of capability.”

Here are four things top forecasters fear will get worse under Trump:

Lead time

Lead time is the currency of extreme weather forecasters and emergency managers.

“The longer lead time that you have, the more you can do to protect lives and property,” said James Franklin, a former forecast chief at the National Hurricane Center.

As a rule, tropical storms and hurricanes have days of lead time compared to the minutes for severe thunderstorms and tornadoes. Hurricane forecasts have vastly improved throughout the years, now giving communities two extra days of forecasts to prepare to evacuate.

The National Hurricane Center set records last year for how accurate their forecasts were. Now, they are working to extend the 5-day forecast to seven. It’s unclear how much work will or can be done toward that goal as the Trump administration cuts NOAA workforce.

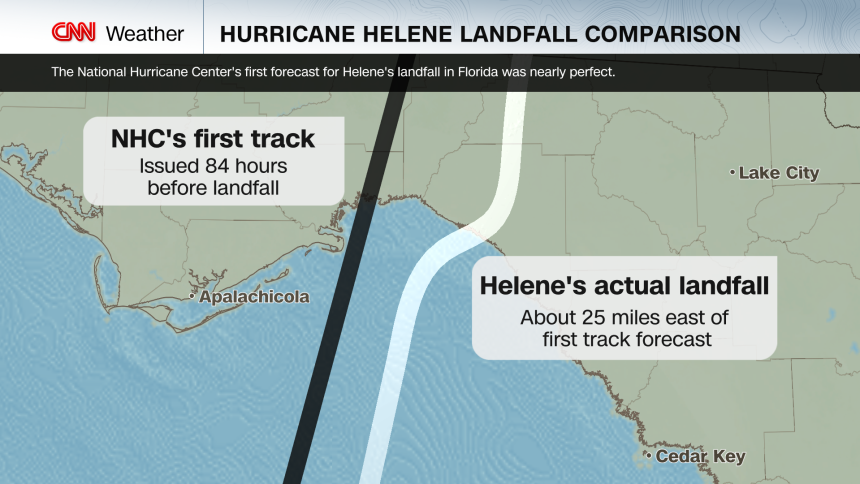

Hurricane landfall

Forecasters are also getting better at pinpointing where storms are going. They do this by using satellites, weather radar, ocean sensors and by flying an airplane directly into the eye of the storm.

Hazelton, the hurricane hunter fired as part of a wave of firings targeting probationary employees at NOAA, said the flights give meteorologists a “pretty unique data set” that they can’t otherwise get from satellites or other tools.

That data includes precise measurements of wind speeds inside a storm’s eye wall — where its strongest winds roar around its center — and its pressure. These measurements help forecasters determine exactly how strong a storm is and if it’s starting to get even stronger. The storm’s strength impacts its ultimate track.

Being able to narrow down where a storm is going to hit is crucial because it allows emergency managers to evacuate some areas and tell others to stay put.

“You could leave New Orleans or Miami or some other big area out of an evacuation zone, because your forecasts are more precise,” Franklin said. “That’s a tremendous saving.”

Rapid intensification

Forecasters and emergency managers have watched with alarm over the past few years as storms, including hurricanes Helene and Milton, have ballooned into monster systems in a matter of hours, fed by record-warm ocean heat.

Scientific understanding of rapid intensification has gotten better in part because NOAA invested in measuring ocean temperature, Spinrad said, adding major advancements were made after the devastating 2005 Hurricane Katrina.

“We always thought that the sea surface temperature was the key to understanding intensification, and it turned out it’s not the sea surface temperature, it’s temperature of the whole ocean,” Spinrad said. “You can’t tell how hot the pudding is just by measuring the film on the top.”

Once scientists understood they also needed to measure temperatures deeper in the ocean, they were able to improve their rapid intensification forecasts, Spinrad added.

As the planet warms, storms are getting stronger and more complex – feeding off warm water and holding more moisture in the atmosphere. Cutting staff and potentially pulling ocean sensors out of the water will kneecap forecasters and scientists at the worst time, experts said.

Free, accessible data

National Weather Service data and forecasts are public and free. Its data serves as the basis for many private weather apps and alert systems. Other countries, including our allies, use it, too.

Former forecasters said keeping robust and accurate weather data free is essential for public safety and private industry.

Just as essential is having humans who can communicate forecasts to the public, especially as climate-fueled storms get more complex.

“Local weather service forecasters typically know the media really well, they’ve worked with them for years,” Stensrud said. “Also, emergency managers and towns develop personal relationships, so there’s a level of trust that develops over time.”

Sudden cuts to the weather enterprise makes Stensrud “very worried,” he told CNN.

“Worldwide, the US is the best at forecasting for severe weather, and we’ve developed the current system over time,” Stensrud said. “When you’re making cuts to it, or you have to adapt so quickly, the potential for cutting in ways that are hurtful goes up.”