Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

(CNN) — Beneath the rough waters of South Australia’s coast, marine archaeologists say they have discovered the lost Dutch merchant vessel Koning Willem de Tweede, which sank nearly 170 years ago. The wreck captures a tragic moment in maritime history during the 19th century Australian gold rushes.

The 800-ton sailing ship was beginning its journey back to the Netherlands in June 1857 when a severe storm capsized the vessel near the port town of Robe, according to a news release by the Australian National Maritime Museum. Two-thirds of the crew drowned.

Just days before, 400 Chinese migrants headed for gold mines in Victoria disembarked from the ship. The crew transported the laborers as a “side hustle” for extra money, according to James Hunter, the museum’s acting manager of maritime archaeology. The practice was a common but questionably legal voyage at the time, he said.

While the captain lived to tell the tale and litigate his losses, the bodies of his crew members remain lost in the sand dunes of Long Beach.

However, on March 10, after three years of searching for the site of the wreck, a team of divers supported by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Netherlands’ Cultural Heritage Agency spotted what they say is the sunken vessel.

“There’s always a little bit of luck in what we do,” said Hunter, who was the first diver to see the ship underwater. “The sand had just uncovered just a little bit of that shipwreck so that we could see it and actually put our hand on it and say ‘we’ve finally got it.’”

The expedition team members say they are confident they’ve found the Koning Willem de Tweede based on its location, which matches historic accounts of the wreck, and the length of the metal pieces detected, which matches the vessel’s documented length of 140 feet (43 meters). Pieces of a 19th century Chinese ceramic were also found in 2023 on the beach near the wreck site.

“Ships were important and expensive, so they were often well-documented,” said Patrick Morrison, a maritime archaeologist at the University of Western Australia who was not involved in the finding. “So when material is found, it can be matched to accounts of the sinking and the ship’s construction, like size, materials and fittings.”

Now, the museum, which partnered with the Silentworld Foundation, South Australia’s Department for Environment and Water, and Flinders University in Adelaide, will search for, recover and preserve artifacts from the wreckage that could reveal more details about 19th century shipbuilding, the crew and its passengers.

A finding anchored by history

Due to its long history as a global maritime trading mecca, Australia is a hot spot for shipwrecks, with an estimated 8,000 sunken ships and aircraft lying near its coasts. Some of the ships date to the 1700s, when colonization first began, according to the Australian government’s Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water.

The discovery of gold mines in Victoria sparked a migration of Chinese laborers in the 1850s, leading the Victorian government to levy a £10 tax, worth over $1,300 (£1,000) today, on every migrant who entered its port, according to the Dutch Australian Cultural Centre.

To avoid this tax, agents in China would often pay for European merchant vessels to transport the migrants to other Australian ports, according to the National Museum of Australia. Upon arrival, the migrants were met with discriminatory treatment, and many were not successful in the mines, still owing a large portion of their earnings back to the agents.

The Koning Willem de Tweede was meant to do trading between the Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies, a former colony that’s now Indonesia. However, just before returning home, the crew picked up the Chinese migrants from Hong Kong and dropped them off at Robe, a community about 365 miles (400 kilometers) west of the main ports in Victoria, from which the migrants trekked overland to the gold mines, Hunter said. To this day, it’s unclear from the police reports, crew accounts and court records whether this voyage was sanctioned by the ship’s owner.

What is clear, however, is the community of Robe’s storied dedication to answering questions about the wreck and the lost crew members, he added.

As massive waves battered the ship to pieces, an Indigenous Australian man on land attempted to swim a rope out to the ship to save the captain but just couldn’t make it in the surge, Hunter recounted. “So the captain wound a line around a little barrel, and he threw it into the water, and the townspeople who had gathered on the beach grabbed the line and pulled him through the surge and he survived.”

If the bodies of the crew members are recovered, Hunter said the Robe community will likely create a proper burial place for them.

“Shipwrecks reveal Australia’s long-standing maritime connections with the rest of the world, connections reflected in our towns and cities today,” Morrison said. “I hear the team is planning to return. I’m sure each visit will reveal a new part of the story.”

What remains of the ship?

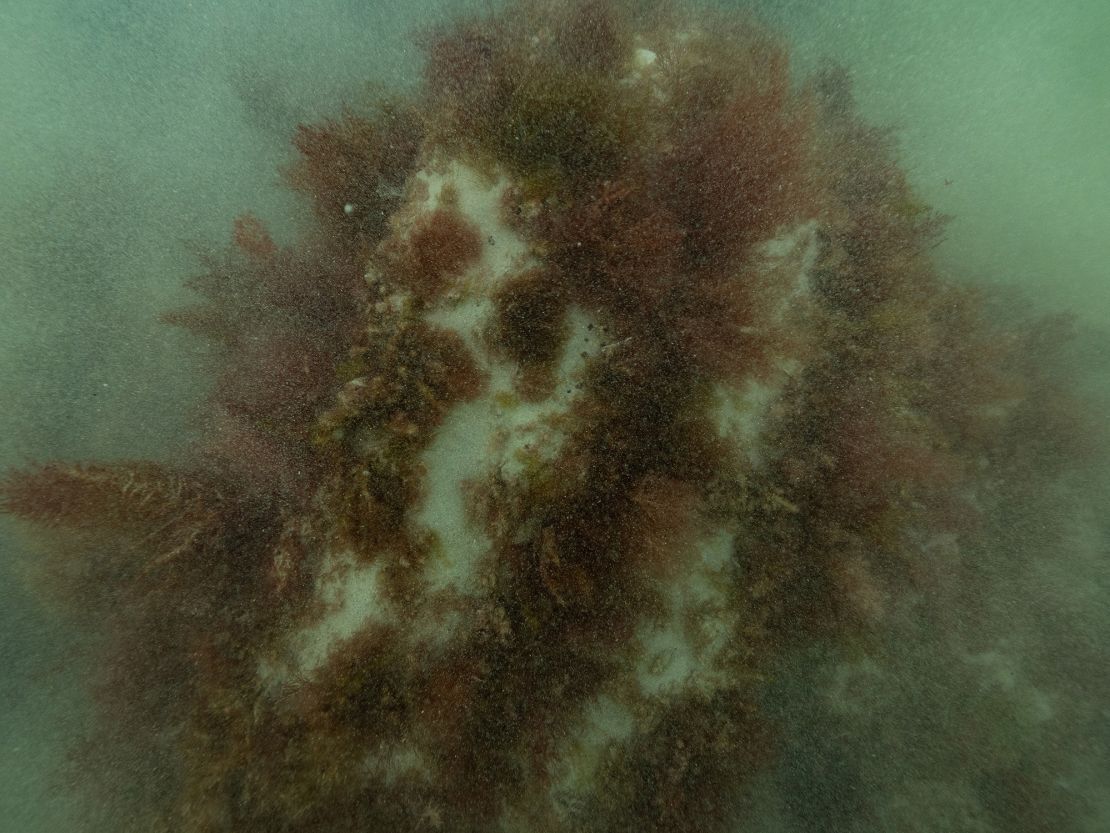

It’s still too early to tell, but Hunter said most of the ship’s hull structure appears to be intact beneath layers of sand.

Using metal detectors and magnetometers, the team was able to locate large bits of steel and iron protruding from the seafloor that turned out to be parts of the frame and windlass, the machine used to reel in the anchor. Long planks of wood thought to be from the upper deck of the ship lie nearby, Hunter said.

“(The hull) could teach us a lot about how these ships were built and how they were designed, because with that sort of information, there’s not a lot of detail in the historical record,” Hunter said.

Since the Koning Willem de Tweede sank hundreds of yards from the shore, the crew was not able to go back and recover their personal items, so it’s possible the researchers could find coins, bottles, broken pottery, weapons and tools, according to Hunter.

Items recovered from the shipwreck must be retrieved carefully so they don’t immediately disintegrate upon reaching the surface, said Heather Berry, a maritime archaeological conservator for the Silentworld Foundation, in an email.

“As always, shipwrecks rarely occur in calm waters,” Berry said. “The surge on the site is such that often you have to hold on to something sturdy to keep from being swept away, so we would need to ensure we don’t accidentally grasp on to something fragile.”

The recovered artifacts are placed into tubs full of seawater that are then gradually desalinated to reduce the corrosive effects of salt upon drying.