CNN

—

Only 26 African countries had achieved independence when, in February 1961, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie ascended a sloping staircase to inaugurate Africa Hall in Addis Ababa, which he gifted as the new headquarters for the UN Economic Commission for Africa (ECA).

A dominating presence in the heart of the Ethiopian capital, adorned with a sweeping 150-square-meter (1,614-square-foot) stained-glass window, the structure, designed by Italian architect Arturo Mezzedimi, had taken just 18 months to build. Fittingly then, it didn’t take long before the building became the site of a landmark event in the story of modern Africa.

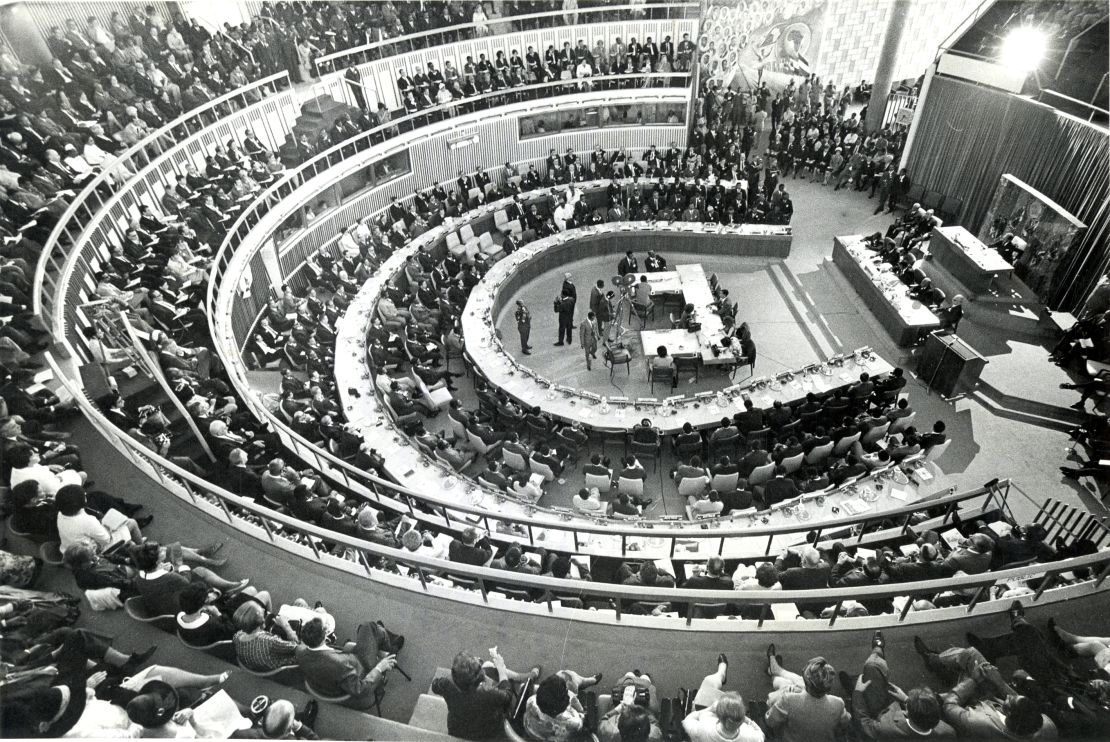

Just over two years later, Selassie once again made the climb to welcome the founding members of the newly formed Organization of African Unity (OAU) to their home — a meeting place intended to foster cooperation, drive economic progress and eradicate colonialism across the continent.

Addressing representatives of the then-32 independent African states, Selassie declared that the continent was “at midcourse, in transition from the Africa of yesterday to the Africa of tomorrow.”

“We must act to shape and mold the future and leave our imprint on events as they slip past into history,” he continued.

More than 60 years later, Selassie’s message has come full-circle: Africa Hall has been shaped and molded anew.

Last October marked the completion of a decade-long renovation across the entirety of the 12,800 square-meter site, commissioned by the ECA in 2013 with a $57 million budget to revitalize the landmark as a world-class conference and cultural venue.

Australian design practice Architectus Conrad Gargett was entrusted with leading the re-design, giving project architect Simon Boundy a mission with dual themes — modernization and conservation.

“The two go hand-in-hand with projects like this,” Boundy told CNN, “Where you’ve got an aging asset, but if it doesn’t get used, it falls into disrepair.”

“It’s about bringing the building back to life, making it accessible to the public and celebrating the story of the building for future generations.”

Building balance

The conundrum for Boundy and his team was that those two aims threatened to undermine the historical significance of Africa Hall. In essence, how do you modernize a historical landmark without losing some of its soul?

As a heritage architect — regularly tasked with making sensitive changes to buildings of historical or cultural importance — Boundy is well-versed in answering that question.

The first step was understanding Africa Hall’s importance and history, which was aided by hiring local architects and engineers to work on the renovation. Among them was Mewded Wolde, who, a day before her university graduation in 2014, found herself on the roof of Africa Hall taking measurements.

Born and raised in Addis Ababa, Wolde says the building — which hosted OAU meetings until the organization was replaced by the African Union (AU) in 2002, which eventually moved into new headquarters in Addis Ababa — is a source of pride for herself and many others given its role in helping countries across the continent achieve independence from colonial rule.

“This building, still for the African Union, is a symbol,” Wolde told CNN.

“It’s an artwork in itself that symbolizes the struggle that we have gone through in the past 60, 70 years to get to African unity.”

Local knowledge helped Boundy navigate the “balancing act” of modernizing Africa Hall without devaluing its legacy. Roughly 13 million new tiles were fabricated and reinstalled to exactly match the original material, staying true to the brown, orange and off-white color palette of Mezzedimi’s modernist design.

The old layout of the Plenary Hall was deemed to lack seating space, so after consulting the building’s original architectural drawings, the team designed new furniture in the same style and added an extra ring of seating.

Hidden in each desk is a digital screen, a subtle addition that — along with the arrival of a 13-meter-wide (42-foot-wide) LED display — leaves Africa Hall well suited to meet the technological requirements of modern conference hosting, while preserving the original architecture.

“We don’t want to leave our mark on the building,” Boundy said. “We want to just bring the original design to life again and hopefully everything that we do is behind the scenes, concealed in the ceilings, and it’s not the feature.”

Some aspects, however, demanded more radical change, especially those concerning accessibility and safety. The building — “quite dilapidated” — was stripped back to its structural core and strengthened with carbon fiber and steel before being built up again, Boundy explained, to protect the concrete from the damage caused by rusting steel and the threat of seismic activity.

Total Liberation

Protective measures also included a strengthened frame for the crown jewel of Africa Hall: the two-story stained-glass window that has adorned the foyer since 1961.

Titled “The Total Liberation of Africa,” it was Ethiopian artist Afewerk Tekle’s signature piece and is split into three panels; Africa Then, Africa Then and Now, and Africa Now and in the Future.

Featuring a knight in shining armor emblazoned with the UN logo, a dragon and the grim reaper, the work tells a story of liberation, of “slaying the demons” of colonization, Boundy explained.

Tekle’s work is Africa Hall’s definitive symbol, and can be seen splashed across shirts, ties and more in the city.

“The symbolism of the artwork is something that’s really hard to overstate, how important that is,” Boundy said.

“It really tells the story of what Africa Hall is trying to represent, which is the very best of what Africa can do, quite literally shedding the recent history, and looking very much forward … You can sit and spend hours staring at it.”

With various original pieces either loose or missing, the entire artwork was meticulously disassembled, cleaned and restored panel-by-panel by Emmanuel Thomas, the grandson of the person who originally made the stained glass from Tekle’s design.

Its refreshed look was unveiled alongside a new permanent exhibition to highlight the key events at Africa Hall that have helped to shape Pan-African history. For Wolde, both the artwork and the renovation itself are reflective of Selassie’s 1963 address, where he spoke of molding the Africa of tomorrow.

“Even now, even with all the upgrades that have happened in Africa Hall, this quote is actually true,” Wolde said.

“This is the space that we’re going to use to shape the future. Even then it was where they were having meetings … to shape the future of Africa, and even now, it symbolizes that. I really love this.”